The aftermath of a suicide is an endless tunnel – of pain, regrets and questions.

Could something have been done to stop him? Why did she do it? What warning signs were there?

The act of taking one’s life leaves no easy answers for those left behind.

“The majority of people who are survivors spend the rest of their lives not talking about this and suffering in silence,” said Mike Brose, executive director of the Mental Health Association in Tulsa, which will soon rename itself as as statewide group. “You don’t necessarily get over it, but you can get better.”

Oklahoma has a suicide rate that is higher than the national average and was 12th highest among all states and the District of Columbia in 2010, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Both Oklahoma’s and the nation’s rates are increasing. The state’s suicide rate rose by 13 percent from 2000 to 2010, according to the CDC. And now, partly because of a rise in suicides among baby boomers, suicide is one of the leading causes of death among nearly all age groups. In 2010, more than 600 people committed suicide in the state.

More funding for programs and better understanding of mental illness are crucial, Brose said. But his association also is mounting an effort to give people the basic skills for how to recognize and respond to a relative, friend or other person who may be suicidal.

The approach is called QPR – “Question, Persuade and Refer,” and the hope is that it will become as widely accepted as CPR.

QPR training outlines ways to persuade individuals to seek help and provides resources for referral.

“It’s an attempt at getting people much more comfortable than they typically are around this issue,” Brose said. “I’ve heard it over and over again from survivors, ‘I didn’t know what to say.’”

Brose’s organization in Tulsa is expanding its reach beyond the city, filling gaps created by the Oct. 31 closing of the Mental Health Association of Central Oklahoma in Oklahoma City.

The Tulsa group is changing its name to reflect its broader mission and will take over at least two programs the Oklahoma City association had provided. One program provides free mental health services to low-income people and a second screens teenagers for mental health issues.

Meanwhile, the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services is developing its own suicide prevention plan, using $500,000 in state funding in addition to federal grants.

A BOY'S DEATH

Nearly a decade after her teenage son killed himself, Michele Magalassi of Owasso painfully recalls Brandon’s behavior in the weeks before his death.

His birthday was approaching, and birthdays in the family were big events. This time, Brandon, then 14, was not interested in planning anything.

“He was tired all the time, withdrawn from the family. He was just not engaged,” Magalassi said. “Had I known more about depression, I would probably have asked more questions … We just had no idea that he was that volatile.”

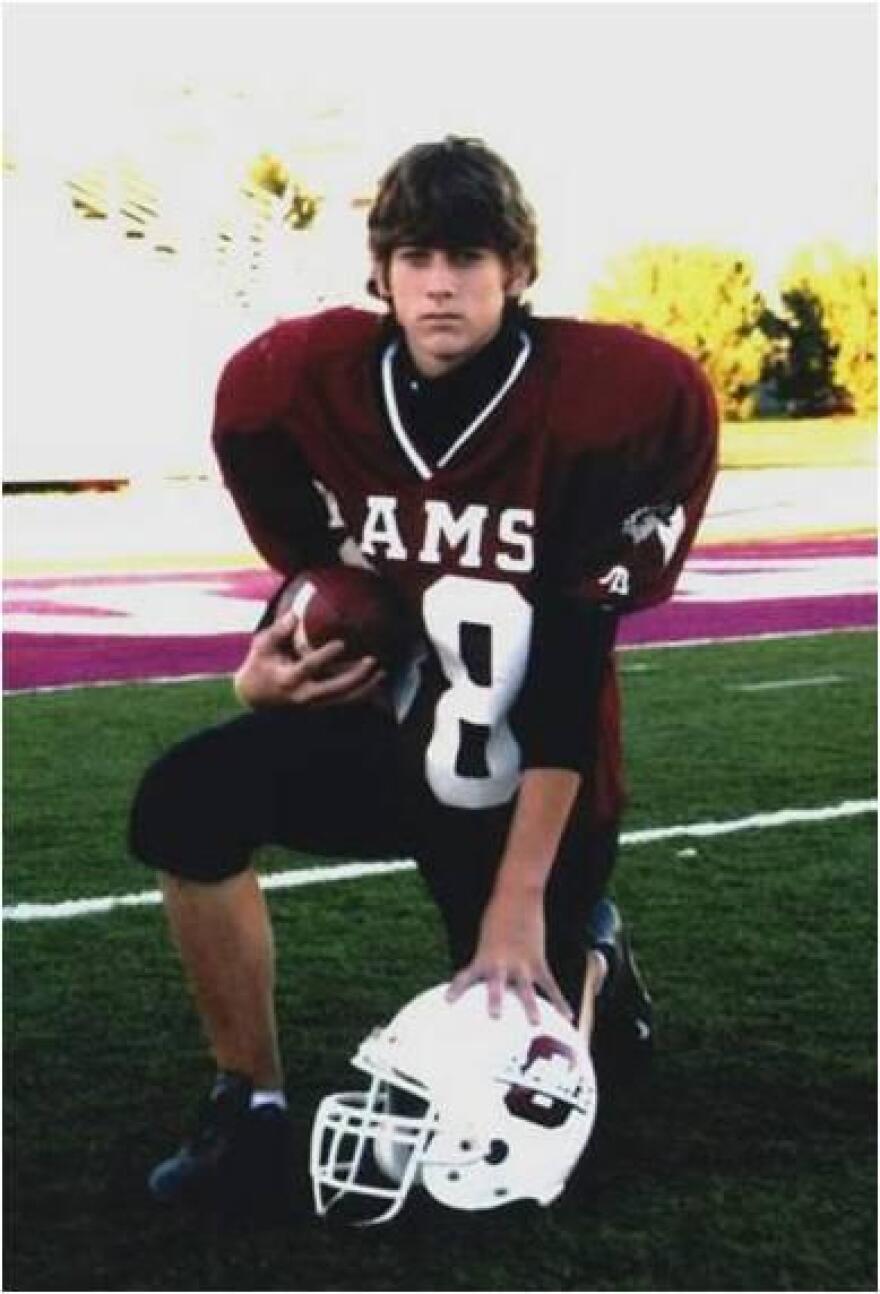

On May 26, 2004, Brandon, a popular honors student and football player, got into some trouble at school, along with others, for writing in a student’s yearbook. His father, Billy Magalassi, picked him up, took him home and returned to work. Brandon’s brother Justin was home, but left to go to the school field house.

Alone for that short time, Brandon scribbled a suicide note and then shot himself in the temple. He died more than a week later at St. Francis Hospital.

“We were blindsided,” Michele said. They had viewed Brandon’s behavior as a typical adolescent mood swing, not a mental-health crisis.

MENTAL ILLNESS

Suicide rates are often an indicator of the prevalence of mental illness in a state.

About a decade ago, a study by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that Oklahoma had one of the highest rates of mental illness in the country. Yet people who suffer from mental illness, including depression, often do not seek help, Brose said.

High suicide rates are attributable to factors such as a lack of access to mental health care and lingering stigmas about mental illness, said Rachel Yates, director of suicide prevention and outreach programs at HeartLine, a crisis resource center.

“A lot of people don’t reach out because they fear the judgment. They fear being called crazy or nuts,” Yates said, adding, “It’s been such a taboo topic for so many years.”

That's where QPR training is supposed to come in.

Yates, a certified QPR trainer, has taught the free one-hour training course at universities, military bases and support groups.

Part of the goal is to break through misperception that talking with someone about suicide increases their chances of acting on suicidal thoughts.

“People are scared. They don’t have a lot of confidence around this topic, so they do nothing,” Yates said. “Talking about it can reduce one’s risk (for suicide), rather than increase it.”

Brose said his organization is also seeking corporate partners to help implement the approach, which can be included in a range of occupations’ training programs.

QPR training has been used in police academies, teacher training courses and even cosmetology schools, Brose said.

“Anyone can learn,” Brose said. “If we’re really going to have an impact of bringing the horrific numbers of suicides down, we’re going to have to do a much better job of educating and training the general public.”

THOSE LEFT BEHIND

Michele Magalassi’s voice still falters frequently often when she recalls her her son’s death and the effects on the family. Justin was angry. Michele and Billy sought counseling. And then gradually, relying on their Christian faith, pastor, friends and others, the Magalassis began to move forward again in life.

They decided “we’re just not going to let this tragedy break our family up,” Michele said. “This is not going to get the better of us.”

THE GUN FACTOR

One factor in suicide rates is the availability of firearms. Brose said that in homes with guns, the chances of a successful suicide attempt increase because a firearm’s lethal efficiency leaves little room or time for someone to reconsider and stop.

More than 60 percent of all suicides in Oklahoma were carried out with a firearm in 2010, according to federal data.

“We’re not trying to interject ourselves into the gun-control debate,” Brose said. “It’s not about that argument.”

He notes that use of gun locks or gun safes can help deter individuals who may be contemplating suicide. If people who start to act on suicidal feelings can be deterred for at least 30 minutes or an hour, it may save their lives.

“There are a number of suicide attempts and completions in this country that are done spontaneously,” Brose said. “Often times people change their minds… and suicide is averted.”

The Mental Health Association sponsors support-group meetings at its Tulsa office twice a month for survivors of suicide.

“There’s going to be a suicide in the state today, somewhere. Probably more than one,” Brose said. “It’s a death that affects people like no other death. People spend the rest of their lives trying to understand it and asking themselves why.”

HELPING OTHERS

Brandon’s suicide has led the Magalassi family to reach out to others.

The couple started the Brandon Magalassi Memorial Scholarship Foundation, which awards $1,000 scholarships to Owasso-area high school seniors who write essays on suicide prevention. The foundation also sponsors “Shadow Run” education events that focus on problems that may lead to suicide, such as cyberbullying.

They talk to other parents whose children have committed suicide, although not all the parents want to talk.

“I just hope it helps,” Michele said of the couple’s efforts. “We just never know who it’s going to touch.”

______________________________________

FOR MORE INFORMATION

• For information on mental health services offered in Oklahoma communities, call a community referral assistance line at the mental health association in Tulsa, soon to rename itself as a statewide group, at (918) 585-1213 from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.

• Individuals seeking suicide outreach programs, compassionate listening, crisis intervention services or information and referral services can call HeartLine’s 211 service.

• For information on QPR training, contact the mental health association at (918) 585-1213 or HeartLine at (405) 840-9396.

• To reach national suicide prevention hotlines, calls 1-800-SUICIDE or 1-800-273-TALK.

______________________________________

KGOU relies on voluntary contributions from readers and listeners to further its mission of public service to Oklahoma and beyond. To contribute to our efforts, make your donation online, or contact our Membership department.