Bonds are complicated, and even one of their most vocal fans admits they lack razzle-dazzle.

"Maybe these projects are a little less sexy, but they're the ones that kind of impact your life the most," Oklahoma City Mayor David Holt said.

So ahead of Oklahoma City's historically big bond election next Tuesday, we're breaking down bonds to better understand how they work in Oklahoma and why they're so important to local government operations.

What exactly is a bond?

Municipal governments in Oklahoma face an unusual funding situation compared to their peers in other states: the Oklahoma Constitution prohibits them from levying property taxes for city operations.

Instead, local governments primarily use sales tax revenue to cover expenses like staff salaries. But when it comes to improving infrastructure like roads, transit and drainage, they've got one option: bonds.

Though cities and towns are barred from using property taxes for everyday funds, they can ask voters to approve them on a case-by-case basis for specific city projects. The upcoming Oklahoma City bond package does just that. In eleven separate votes on the upcoming ballot, the city asks residents to decide whether OKC should go into debt to fund structural upgrades and then pay back that debt using property taxes.

Camal Pennington, the councilman for northeastern OKC's Ward 7, stresses that there aren't other options for these projects if voters reject the bond package.

"Our only opportunity as a city to make meaningful investments in infrastructure comes in the GO bond," Pennington said.

General obligation, or GO (pronounced gee-oh), bonds don't require assets as collateral — it's just the city's promise to pay back the debt with taxpayer dollars. Holt points to the city's consistently high bond ratings — which he attributes to strong financial management — as a key factor in allowing interest rates to remain low.

To Holt, the passage of the bond package isn't just a want, it's a need.

"These projects are like meat and potatoes stuff. This is not the initiative for dreamers," Holt said. "This is the initiative for people who understand that you just got to invest in the basic needs of your city. "

In order to aid its passage, Holt and the rest of the city council have settled on a proposal that doesn't increase property tax rates. It instead extends the current tax rate, which was established during previous bond packages. It relies on increasing property values and population growth to generate more revenue than previous bonds.

A checkered past

Bob Blackburn, the former director of the Oklahoma Historical Society, said the city has been bonding for well over a century. But those efforts were met with limited success until recent years.

It all goes back to Oklahoma's agricultural roots.

"Oklahomans don't like taxes, and especially property taxes. Farmers lost their farms because of property taxes they couldn't pay when a crop failed, or a railroad raised their rates to get their wheat or cotton to market," Blackburn said.

As the state became less reliant on farming, bonding projects still faced challenges. In the 1980s, financial turmoil in the oil sector led to reluctance toward taxes. And almost 20 years later, the passage of the first Metropolitan Area Projects (known as MAPS) initiative didn't come without a fight, Blackburn said. However, it was this event that changed the tide for bonds.

Although MAPS is a sales tax, not a bond, its first iteration in 1998 brought the city a sense of excitement around community projects, like the Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark and the Bricktown Canal. The success of MAPS in the eyes of voters strengthened their trust in the ability of the city government to use their money wisely, Blackburn explained.

"That was the first that really broke the logjam of this community's lack of willingness to support communal projects to go forward," Blackburn said. "And then MAPS was successful, and the political elite gained the confidence of the people."

Since then, the city has passed multiple bond packages, including ones in 2007 and 2017. As the city has grown in population and property value, its dollar amount has increased. This year, OKC residents have the option to pass the biggest one yet, at $2.7 billion.

What's in the bond package?

Oklahoma City Public Works Director Debbie Miller said thinking about the scope of the bond package gives her chills.

"It's a lot," Miller said. "But there's a lot of need. When we initially had the initial list, it was $9 billion, everything that was on there. So, you know, we kind of had to pare it down."

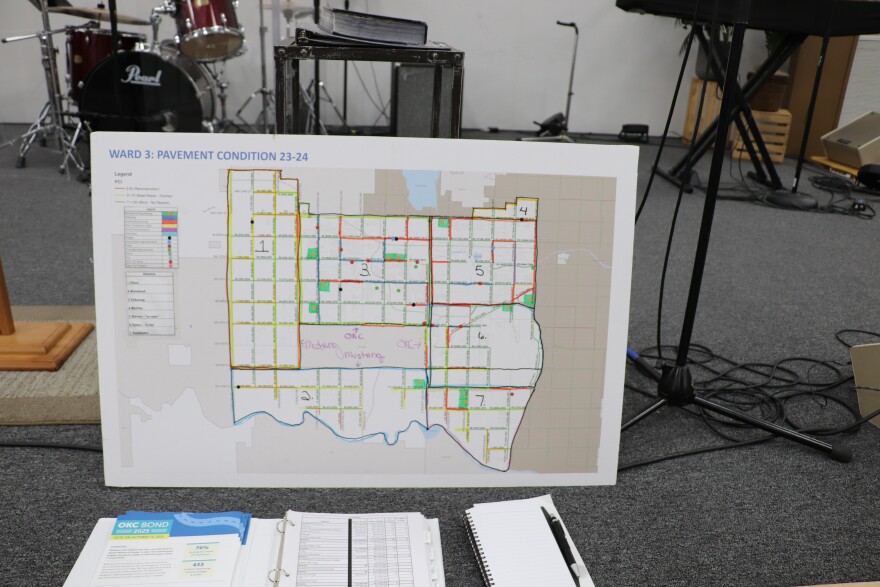

With Miller at the helm, city staff combed through data on repairs and pavement quality indices to identify where investments were needed.

"They have an objective system for reviewing the quality of roads, of bridges," Pennington said. "They know where they have received the most complaints regarding drainage. And so then they make a priority list based on those conditions and then present it to the city council for us to make decisions based on feedback that we're getting from our constituents, or our own ideas about where we want to see the investment go."

Miller said city officials also asked the public to go online and drop pins in spots they thought could use the help.

By the end of the input period, more than 6,000 pins dotted the map.

"It was really gratifying that when we took that information and overlaid it with what we had determined, it matched up pretty well," Miller said.

Ultimately, all the bond projects have to be approved by OKC's city council before they're presented to voters.

The city identified 547 projects to pay for with the bond package.

Those projects are sorted into 11 bond propositions, and voters will consider each one individually when they head to the polls next week.

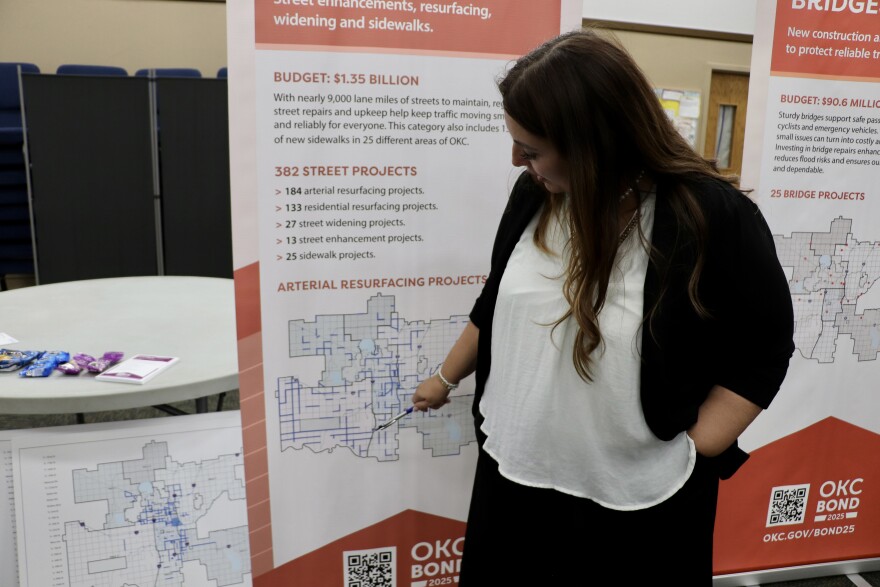

- $1.35 billion for streets

- $90.6 million for bridges

- $81.0 million for the traffic system

- $47.1 million for city maintenance, data and municipal support facilities

- $175 million for economic and community development

- $414 million for recreational facilities

- $52.5 million for libraries and learning centers

- $140 million for the drainage control system

- $130 million for the transit and parking system

- $107 million for police, municipal courts and family justice facilities

- $130 million for fire facilities

Bonds aren't that interesting

Because of their unglamorous contents, OKC bond elections don't tend to stir the same emotions as, say, last year's vote to raise sales tax for a new basketball arena.

OKC bonds have received strong voter support for the past quarter-century, and Holt said the public response to this package seems similar.

"If nobody's against it, like, are people excited about it?" Holt said. "Well, that's probably strong as well because, you know, it's a little it's a little mundane. It's the basic governance of a city."

Each city council ward hosted a town hall or an open house to answer questions about the bond package. Pennington hosted the first of those gatherings in Ward 7.

"I really want our neighbors to be informed about what's happening in our community and about the great opportunity that the bond presents for us to get real investment in the things that I often get my neighbors to complain about," Pennington said.

Joanne Davis attended the Ward 7 town hall and was impressed by the turnout.

"I was so glad to see how many people are involved and want to be involved," Davis said. "That's the important thing, so that when our city officials understand that this is of interest, then they become more interested."

Davis is also happy about the improvements to walkability and safety bond-supported projects would bring to her neighborhood.

She thinks those little things add up.

"All of those things increase my property value, and therefore even how I like my neighborhood," Davis said. "And a lot of times it's, you know, I like my neighborhood, I like my house, I like my street. And guess what? I stay in Oklahoma."

There's a flipside to bolstering property values, though. The bond package wouldn't raise the property tax rate, but people will still pay higher property taxes if their home values increase.

Sarah Carnes lives in Ward 3 — the city's southeasternmost section. At the time of the Ward 3 townhall, she said she was only planning to vote yes on streets, drainage and maybe traffic systems.

"They haven't done, in my opinion, due diligence with the money of the constituency," Carnes said.

In particular, she isn't happy with how Ward 3 has been prioritized during prior bond projects. She highlighted their lack of a library or a recreation center, and a single city-owned park.

"Who's going to have the priority?" Carnes said. "It needs to be out here because we're bringing in houses, apartments, 55-and-up living. We're growing super fast. But we don't have the just simple community necessities of having healthy lifestyles."

Ward 3 Councilwoman Katrina Avers took office earlier this year. She said securing additional bond project funding for her area was a significant motivator for her campaign.

"I had spoken with our existing council member, and she indicated that despite being one of the fastest growing and largest wards, that we were initially slated for some of the lowest infrastructure investments," Avers said. "That was kind of a trigger of, well, that's absolutely not right."

But Avers is happy with the bond package now.

"We have the largest road improvement program that we've ever had in Ward 3," Avers said. "We have a drainage plan to help with the Overholser overflow, as well as our Mustang Creek flowback and drainage basin. And then we have a police and fire station coming over here to the west side, which we're very excited about."

Holt said that although each ward isn't getting the exact same amount, the city council tries to divvy up bond funds equitably.

"You don't really want to live in a city where just one ward is awesome and all its infrastructure is up to date and the rest of the city is crumbling," he said.

The council also prioritized not raising the property tax rate, but Holt says that comes with a tradeoff in terms of how quickly the projects can be completed. Some of the projects from the 2017 bond package are still in progress.

"People want it to go faster, but they don't want to pay more for it, and that's not possible," Holt said. "So we're doing it at the pace we can with the taxation level that enough of you are comfortable with."

When to vote, and what happens after

Oklahoma City residents can vote on each of the eleven bond issues next Tuesday, Oct. 14, from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. at their designated polling place, which can be found on the Oklahoma Voter Portal. People can also vote early on Oct. 9 or 10 from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. at the Oklahoma County Election Board.

The bond issues that get approved will go out to auction. Buyers will bid on them, competing to offer the lowest interest rate on the loan.

"It's not going to be precise until the moment we actually sell the bonds, and we'll be in a council meeting when they do it," Holt said. "And then like, we're like waiting for — is the sale over yet? And then we'll approve it all when the sale ends. It's a little dramatic."

If all 11 parts of this bond package fail, the fraction of residents' property taxes that currently goes to the city (as opposed to the county or schools) would slowly shrink over the next couple of decades as OKC pays off existing bonds.

But Holt said those city governance projects wouldn't get done.

"There's no plan B," he said. "If you vote against this, we'll just have to keep asking you until you say yes, or just let the city fall apart, literally. But there's no other way to fund the core infrastructure of the city."

This report was produced by the Oklahoma Public Media Exchange, a collaboration of public media organizations. Help support collaborative journalism by donating at the link at the top of this webpage.