State law allows police to arrest accused domestic abusers without a warrant if there is sufficient evidence, such as a witness statement or a victim’s visible injuries. But a lack of communication among law enforcement agencies is allowing suspects to avoid prompt arrest.

Police have 72 hours after a reported domestic violence incident to make an arrest with no warrant. Law enforcement officials say suspects often flee the scene before police arrive, making it difficult to detain them during that time.

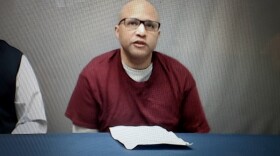

Lt. Clay Asbill, who heads the Tulsa Police Department’s family violence unit, said many abusers have subsequent run-ins with police, deputies or highway patrol troopers within the 72 hours, but aren’t detained because those officers don’t know the suspect is wanted on an abuse complaint.

In August, a Tulsa woman was walking home from the store with her daughter and three children she was babysitting when her boyfriend drove up next to them. The woman thought he would offer them a ride home, but instead he chastised her for leaving the house and punched her multiple times, knocking her to the ground while she was holding an 8-month-old baby, according to a police report.

The man fled the scene before police arrived and later was pulled over by a highway patrol officer for speeding. The officer had no idea that Tulsa police were searching for the man and that there was probable cause to arrest him. In that case, however, the man was arrested for driving under the influence and his connection to the abuse incident was later discovered.

Asbill said Tulsa’s police officers were also missing those types of connections before he launched the “Domestic Caution Indicator” last summer.

Tulsa police started creating profiles for domestic violence suspects in the department’s internal tracking system, TRACIS. which houses incident reports, photographic evidence and witness statements. Officers can make the arrest based on the information in the profiles, which disappear after 72 hours.

Since June, the department has entered 299 suspects into the system and made 41 arrests.

After the 72 hours expires, police must get a warrant to make the arrest.

“The quicker we can get them arrested, the safer that victim is going to be,” Asbill said. “It also increases our chances of our victims cooperating because if their suspect is quickly arrested, they have more faith in the system.”

About 31 state agencies can access TRACIS, but the list does not include the Oklahoma Highway Patrol or Oklahoma City police.

Lt. Dustin Motley, with the domestic violence unit in Oklahoma City, said they have a similar procedure in place. But the system breaks down when a suspect crosses city boundaries or comes into contact with county or state law enforcement officers.

Police in neighboring communities such as Warr Acres or Bethany, sheriff deputies and highway patrol officers cannot access the reports and wouldn’t know to make the arrest, Motley said.

Asbill is working with Rep. Ross Ford, R-Tulsa, on a bill to implement a statewide system for tracking domestic violence offenders. But Ford said budget constraints and convincing law enforcement agencies to work together are likely roadblocks.

“Law enforcement doesn’t always play nicely together,” said Ford, a former police officer. “We like to build kingdoms sometimes instead of focusing on what’s best for our communities.”

Ford said he is researching ways to integrate Asbill’s program into a federal database used by agencies across the state for warrants. The other option is to purchase a new statewide system, which would cost millions and is unlikely to be funded in next year’s budget, he said.

The proposal could also run into objections from groups concerned about defendants’ rights.

Nicole McAfee, director of advocacy for the American Civil Liberties Union of Oklahoma, said increasing non-warrant arrests infringes on suspects’ rights.

“We’re suggesting that increasing officers’ ability to jail folks without a warrant somehow increases safety when data doesn’t suggest that’s true,” McAfee said. “That’s infringing on people’s liberty, rather than focusing on the things that actually disrupt that behavior.”

The state law allowing for non-warrant arrests arose because officials say it can take weeks or months to get a warrant in a domestic violence case, especially if there is a lack of evidence or uncooperative victims or witnesses.

Cindy Hodges Cunningham, an assistant district attorney who leads Tulsa’s team of domestic violence prosecutors, said it typically takes about a week to get a warrant after it reaches her office. But many domestic violence charges are misdemeanors, which may be delayed if prosecutors are tied up with higher priority cases, she said.