The wind whirls through the waist-high grass and between buildings as Cara Brown treads around the George Miksch Sutton Avian Research Center in Bartlesville.

"Prairie chickens in general are at a decline," Brown said. "So, you hear a lot of people, they grew up seeing them all the time and now, they don't see them."

She's a program manager at the center, where scientists work to conserve prairie chickens — including the lesser kind — through surveys and breeding programs. For years, the lesser prairie chicken's habitat has been shrinking largely because of land development, spurring a decline of the species' population.

To protect the bird, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed it under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 2022. But those protections have been removed for the lesser prairie chicken through a recent court ruling this summer. Environmental groups are appealing the decision.

While federal regulations are in flux, conservationists want to see the species thrive in their natural habitats.

"It's an important thing to do what you can, to make habitat suitable and to do what you can to conserve these species and their wild populations," Brown said.

Less prairie means fewer prairie chickens

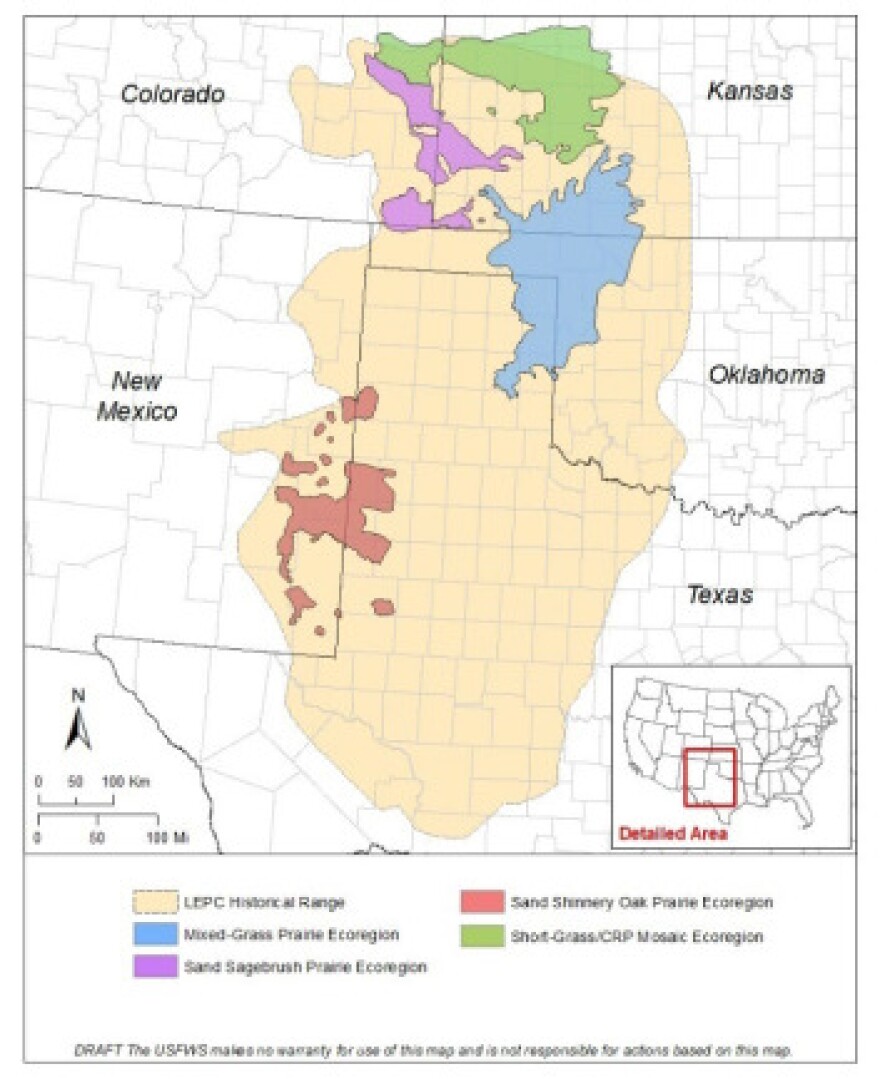

Lesser prairie chickens only live in five states: Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, New Mexico and Colorado.

Researchers such as biologist Fumiko Sakoda, who also works at the Sutton Avian Research Center, say the lesser prairie chicken is an indicator species.

"If they decline, that is a trend which is something wrong with the habitat," Sakoda said.

The Fish and Wildlife Service estimates millions of lesser prairie chickens may have once scurried across a range of almost 100 million acres. But its habitat has been reduced in its historic range by about 90% since monitoring began, leading to a drop in the bird's population, according to the service.

The Western Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies show the birds' population fluctuating over the years. As of 2022, the association estimates the lesser prairie chicken population across all five states is about 26,600.

Sakoda also helps count the lesser prairie chicken population. The bird is found in western Oklahoma and she said the population trends vary at the county level depending on the conservation challenges like land development and tree encroachment.

"Beaver County is the only place we still have the same numbers," Sakoda said. "But only the Harper County was kind of really down. Very down."

Removing federal protections

After President Trump took office in January, U.S. Fish and Wildlife reevaluated its ESA rules. It pointed to flaws in the Biden-era ruling that gave the lesser prairie chicken ESA protections.

On Aug. 12, a federal judge in Texas ruled that Fish and Wildlife made a mistake when determining the ESA status of the species. In 2023, Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas joined a federal lawsuit against the species listing.

"Fish and Wildlife's concession points to serious error at the very foundation of its rule," the ruling reads.

This is not the first time the species has received – or lost — federal protections. The agency previously listed the lesser prairie chicken as threatened in 2014 until it was delisted in 2016.

The 2022 ESA protections separated the species geographically with distinct population segments (DPS).

The southern DPS exists in parts of New Mexico and Texas, while the northern range includes Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado and another part of Texas. Wildlife officials gave the northern population a "threatened" status while the southern was listed as "endangered."

"Threatened" species are not as high-priority as those with an "endangered" status, but they still have certain regulations in what's called a 4(d) rule. The decision strips the listings of both groups.

The lesser prairie chickens in the northern range already lost their 4(d) status, which allows the service to assign specific, enforceable protections to threatened species, earlier this year.

"Fish and Wildlife now believes it erred in applying the DPS Policy and did not provide a sufficient justification that the two population segments of the lesser prairie-chicken are significant for the purpose of identifying a DPS," the document reads.

Attorney General Gentner Drummond celebrated the recent ruling, saying the judge's decision is a victory for the state.

"Oklahoma's cattle grazing, energy production and rural economy are no longer under siege by this unlawful regulation," Drummond wrote in an Aug. 13 press release.

When the state entered the lawsuit, the Oklahoma Farm Bureau supported the move. Rodd Moesel, president of the Oklahoma Farm Bureau, said in August the animals' "threatened" status still allowed regular practices among producers.

He's heard about the prairie chicken for years and said the main concern is the bird's reproductive rate has dramatically slowed. Many producers participate in voluntary conservation efforts.

"In the north, we were still able to continue all the normal farming practices and so, encouraging these voluntary practices to help provide protection for the lesser prairie chicken has been and will continue to be our main effort," Moesel said.

Because the northern population had its 4(d) rule stripped earlier this year, he said the recent lawsuit update would impact the population outside of Oklahoma more.

Environmental groups like the Center for Biological Diversity have pushed back against stripping the species of its protected status.

" The Trump administration, along with the State of Texas and others in the fossil fuel industry who wanted this listing vacated, came up with a pretense to do so, pushed it before the judge, the judge accepted it without any real consideration of the merits," Jason Rylander, senior attorney for the organization, said in August.

Since then, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Texas Campaign for the Environment filed an appeal challenging the decision to strip the species' ESA protections.

"Under President Donald Trump, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reversed its previous support of the rule, alleging there had been a "fundamental error" in the original listing decision," according to a press release from the Center for Biological Diversity. "This was despite the rule having been developed after careful scientific review and public comment."

Working with landowners is crucial, experts say

Regardless of federal flip-flopping, state wildlife officials have practices in place to conserve lesser prairie chicken populations.

Kurt Kuklinski, wildlife research and diversity supervisor for the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, said the department works with landowners and ranchers to improve habitat quality for the species.

"They need wide open grassy spaces, and obviously big cedar and juniper trees growing up in their prairies makes it less inhabitable to them," he said. "So, we focus a lot on vegetation management, especially the woody encroachment of those larger woody species."

Despite the loss of ESA protections, Kuklinski said a multi-state plan is being updated to conserve the species.

"Even though there might not be federal regulations governing what happens with the species, we are still obligated to manage that species to the best of our ability," Kuklinski said.

The court decision is the latest move in a years-long litany of policy switches.

Through it all, state agencies and organizations have worked with landowners to instill voluntary conservation practices because over 95% of Oklahoma land is privately owned.

Kuklinski said landowners generally have good intentions for wildlife on their property because it is an asset and a source of enjoyment to many of them. But the changing rules creates a feeling of nervousness.

"The bird was listed, then delisted, listed again," Kuklinski said. "Now, it's being challenged for a second delisting. That adds greater confusion and uncertainty to landowners. And it creates an atmosphere of maybe distrust is the best word."

Back in Bartlesville, the Sutton Avian Research Center is working on a captive breeding program for the Attwater's Prairie Chicken, a different species that's critically endangered.

The birds are bred at the center and then released in their native Texas habitat. Brown said working with landowners is important for both species conservation efforts.

"One thing we see that's the same with lesser prairie chickens and with the Attwater's is that needing to make connections with the landowners," Brown said.

With this type of breeding program, she said, there are a lot of things that could unintentionally influence the bird's population. She said conservationists hope to prevent this level of intervention in the future by taking action.

"...If you get a species to a point where you have to intervene with a captive breeding program, there's a lot more risk with that," Brown said.

This report was produced by the Oklahoma Public Media Exchange, a collaboration of public media organizations. Help support collaborative journalism by donating at the link at the top of this webpage.