Editor's note: This story has been updated to include the contributions of English teacher Jill Weiler in the publication of Delicious Havoc.

Washington, D.C.'s Capital City Public Charter School feels like a mini United Nations. Many of the school's 981 students are first-generation Americans with backgrounds spanning the globe, from El Salvador to Nigeria to Vietnam. So when the 11th grade teaching team needed to choose a focus topic everyone could relate to and write about, the clear answer was food.

That was four years ago. Since then, English teacher Jill Weiler and her colleagues have joined forces with the staff of the literacy non-profit 826DC, to help students refine their writing (and their recipes), to reach a wider audience.

The process works something like this: Writing coaches ask students to think of a family recipe with a backstory, and then to write an essay around that dish. The recipes (there were a total of 81 last year) and their accompanying stories are compiled into a cookbook of global cuisine with a heartfelt touch, revealing that storytelling may be the most important step in any recipe.

Some students shared tales of beloved dishes, the mere thought of which can make their mouths water. "As the steam from the macaroni rose, the smell seemed as if it had fallen from heaven," writes Mark St. John Pete about his grandmother's macaroni and cheese.

Others focused on less, uh, beloved foods. "I think tamales do not rot because they can be in a fridge for weeks and look the same," says Rolando Fuentes, who lost his taste for bundled packages of corn masa, from his mother's native El Salvador, as a result of what you might call overexposure.

As juniors, many (maybe all) of these students are preparing to head to college. (Since graduating its first class in 2012, 100 percent of Capital City Public Charter School students have been accepted to college.) Writing these food-focused stories has helped the students become better writers, but it's also forced them to delve into their identities and hone their reporting skills with their families, reinforcing important connections before they leave home.

In order to fill holes in their narratives, many of the young writers had to reach out to older family members for more information. When they didn't know a detail or an ingredient, the writing coaches would encourage them to ask. "We'd say, 'Talk to your dad about it," explains 826 D.C's Lacey Dunham. "And they'd say, 'Well I did talk to my dad. We had a conversation, and he told me all this stuff. I had no idea.' "

On the last day of the project, the students celebrated their accomplishment with a potluck — each bringing in the dish they'd so thoughtfully written about. A few even read their stories aloud.

"It's a fun way to get students to think critically about who they are," says Zachary Clark, executive director of 826DC, "to tell their stories through a mechanism where the outcome is everyone gets to eat."

Excerpts from 7 of the 81 stories are below, recipes included:

Okra (Not Orca) Soup, by Chidinma Lantion

Recipe Origin: Nigeria

My mom came to this country on Halloween night in 1990 (she still doesn't understand the purpose of the holiday); it was an experience. She was a petite, wide-eyed 18-year-old Nigerian who had never been out of the country, but who was brave enough to go into the unexpected. She was pushing towards another life outside of what her parents expected of her back home. It was dark and cold, and she felt as if the little children in masks were a projection of what she felt inside. She went to her cousin's house in Rockville, Maryland, and the first thing they tried to feed her was pizza, but she was not having it. There were too many new and unusual flavors that she was not used to, all on one slice that she could not handle it. It just tasted artificial. So she made them go out in the middle of the night to get some okra soup because, after such a long journey to a foreign country, she needed something to remind her of her home and what she was used to. She needed the sliminess of the okra and chewiness of the cow skin to let her know, no matter how far away she was from home, no matter how much things changed, she would always have the comfort that the food would always be the same.

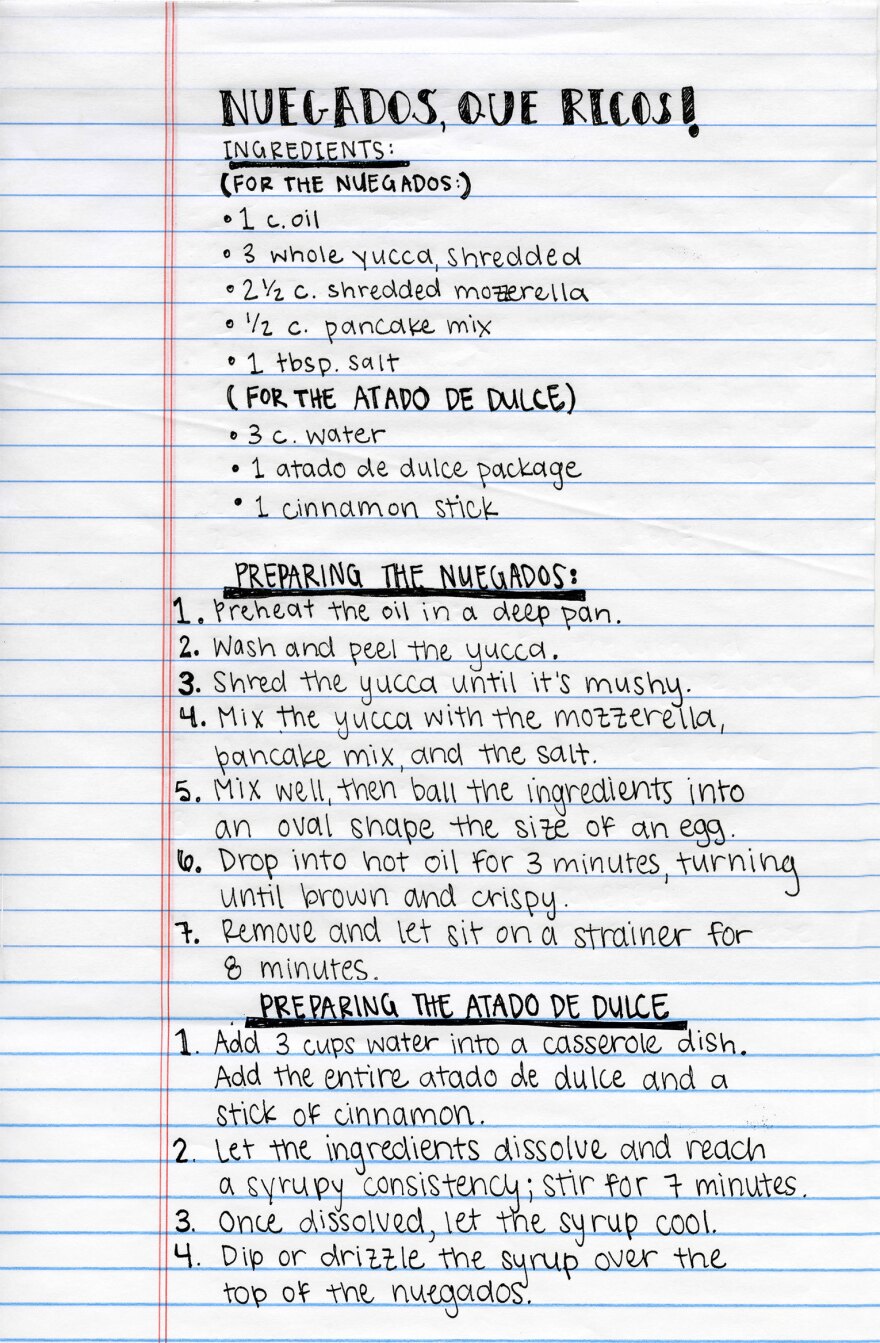

Nuegados, Que Rico! by Janet Arevalo

Recipe Origin: El Salvador

I always helped my mom make nuegados as much as I could ... I would help her peel the yucca with a plastic knife. It took me forever but, you know, safety first. My face would lighten up brighter than the sun when my mom dropped the mushy balls of yucca into the roaring fire. The heat was so intense that over time my mom lost almost all of her lashes. I would help her pack them in bags of five, but I would always take a bite from one of them and put it back in. I called this taste testing for customers, satisfaction guaranteed. My mom would always laugh loudly at my shenanigans, you could hear it from miles away, but she would never get mad. How could I not bite those delicious nuegados itching to be eaten? The smell of the atado de dulce was like a pool of sugar that mixed with my saliva and the rest of the nuegados. (Of course, she took the bitten nuegados out, they had my cooties on them!) Then, after all the food was prepared, my mom would head out to the streets to sell her yummy food to the hungry people.

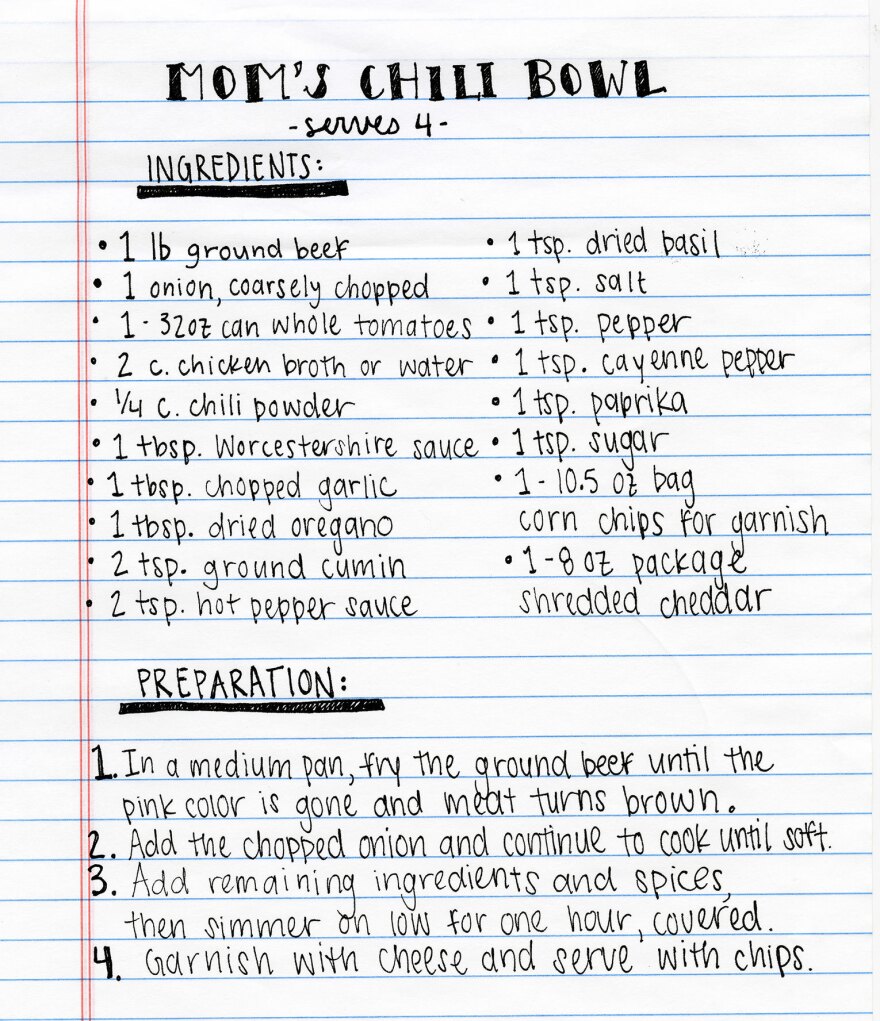

Mom's Chili Bowl, by Idriis Hill

Recipe Origin: United States

As a child in junior high school, my mother loved chili. A couple blocks away from her school, there was a concession stand owned by a man named Mr. Steven. Mr. Steven was a skinny African-American man who wore a hat and had a mustache. He was always happy and took pride in his "shop," which was just a small stand. Every day after school, my mom and a couple of her friends would go to Mr. Steven's hot dog stand because he sold the best chili she ever had. He told her that you couldn't get his chili anywhere because it was his wife's homemade recipe.

After becoming an adult and living on her own, my mother was determined to re-create the chili she remembered from Mr. Steven's stand.

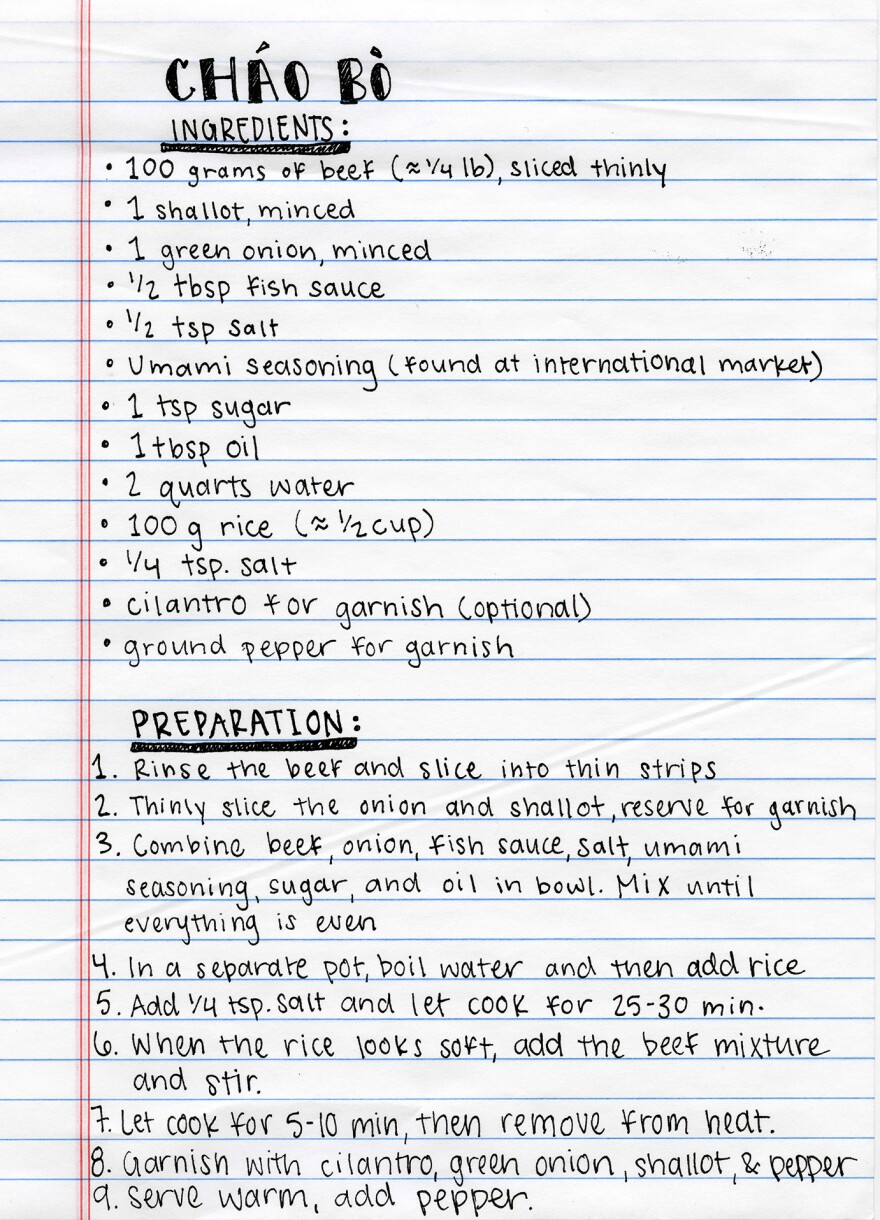

Cháo Bò (Beef and Rice Porridge Soup), by Ana Nguyen

Recipe Origin: Vietnam

In a country filled with many diverse cultures, I always felt like the outcast at school. When there was a potluck for Christmas or Thanksgiving, I was the kid who brought a bag of chips, not because I couldn't bring cooked dishes, but because I lived in a Western culture with a Vietnamese background. I'm in a country mainly dominated by foods my family doesn't normally cook. When I was little, I never ate cereal for breakfast. I would have it as a rare snack, without milk. The few times I brought my culture into the school, I received remarks like, "It looks weird," "It made me want to barf," and "What is that?" ...

One day, two of my close friends came over. They were your average Hispanic-American teenagers. It was mid-July and over 90 degrees outside, around noon. The three of us sat around a small table in the dining room adjacent to the kitchen. Then, my mom brought in cháo for us to eat. The preparations began in my mind. I prepared my mom an excuse as to why they wouldn't eat it. Why I would probably eat most of it. Why I would ask her not to share Vietnamese food with my friends. I watched as they both took a sip of the alien soup. A long silence passed — in reality several seconds — and I hesitantly asked, "How does it taste?" To my surprise they loved it.

The Irresistible Atole de Elote (Warm Corn Drink), by Jose Rivas

Recipe Origin: El Salvador

Even though I was born on March 26, 1999, I feel as if my life didn't start until I was 5 years old. Although many people go as far as to say that they remember everything since they were in the womb — which, by the way, I find a little unreliable — I do have some memories of when I was a little boy. One of my most vivid memories is drinking atole de elote in a small restaurant in El Salvador near the neighborhood where I used to live. Atole de elote is made out of corn and milk. There are some traditional beliefs that surround the making of atole de elote. It's believed that only one person can stir the atole de elote or it will taste bad, and that pregnant women and anyone in a bad mood can't stir it because it will make the atole de elote taste bitter.

See the rest of the 81 recipes featured in 826DC's Delicious Havoc here. To download the recipes in this post, click on the title of the recipe.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.