My name is Beth Wallis, and I’m the education reporter for StateImpact Oklahoma. But not long ago, I was an Oklahoma public school teacher.

In the spring of 2018, my music room’s ceiling was close to falling in from of all the water damage. The classroom next door had an asbestos disclaimer tacked on the wall. Students were sitting on the floor because there weren’t enough desks, rooms or teachers. Entire textbooks were being scanned and copied so there would be enough to go around.

In March, the legislature passed a historic raise for educators and allocated $50 million more to school funding. But by that point, Oklahoma’s education budget cuts were by far the worst in the nation and had a long way to catch up to pre-2008 levels. Many teachers felt like it was too little, too late.

Jennifer Williams now teaches education technology at the University of Oklahoma, but during the walkout, she was a high school English teacher with Oklahoma City Public Schools. Her school, Emerson South, was an alternative school that functioned out of a strip mall.

Her students inherited “cast-off” textbooks from other schools — that is, used and usually damaged textbooks the district didn’t want to surplus. She said her students were very aware of their learning conditions and agreed with the decision to walkout.

“They knew the conditions we were in and they wanted better for people that came behind them,” Williams said. “They’re like, ‘Hey Miss, I don’t want people to use these terrible textbooks. Miss, these desks are awful, we need better. Miss, you all need to be paid better.’ The kids were incredibly supportive. And sure, yes, they got out of school. But for them, that was not the priority.”

So with the situation as dire as it was, it was time to walk.

I participated in the teacher walkout band, banging along on a bass drum to “We’re Not Gonna Take It,” and “Final Countdown” with dozens of other music teachers and band directors. I spent hours meeting with lawmakers and posted my wind-blown and hoarse updates to Facebook.

But after those first few days, that initial hope began to chip away.

Then-Governor Mary Fallin compared the educators in the walkout to a “teenage kid who wants a better car.” Republican Representative Kevin McDugle made a video from the House Floor saying he wouldn’t vote for “another stinking measure” with educators “acting the way they are acting.” I was told by a senator that teachers weren’t his constituents.

Even though national media framed it as a victory, for many teachers, the walkout didn’t feel like a win — more like the opposite. After two weeks, I left Oklahoma City discouraged and disillusioned. For years afterward, it felt like a punch to the gut every time I drove by the Capitol building.

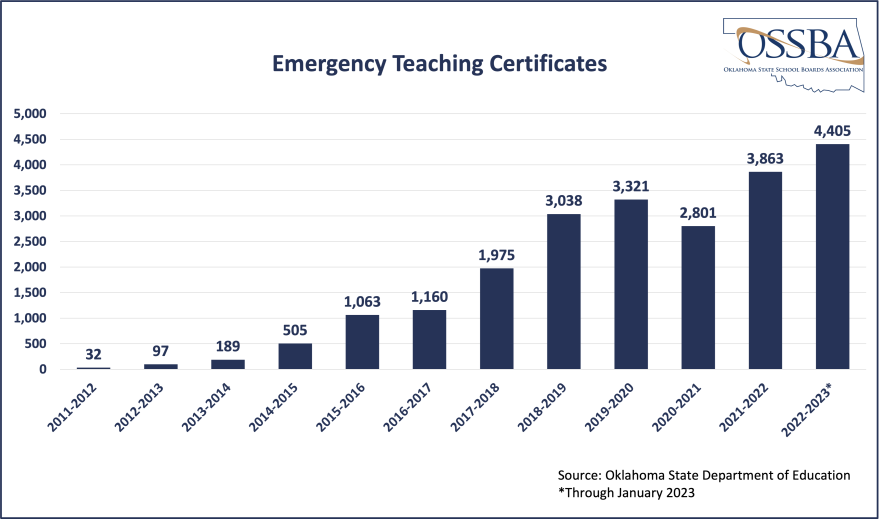

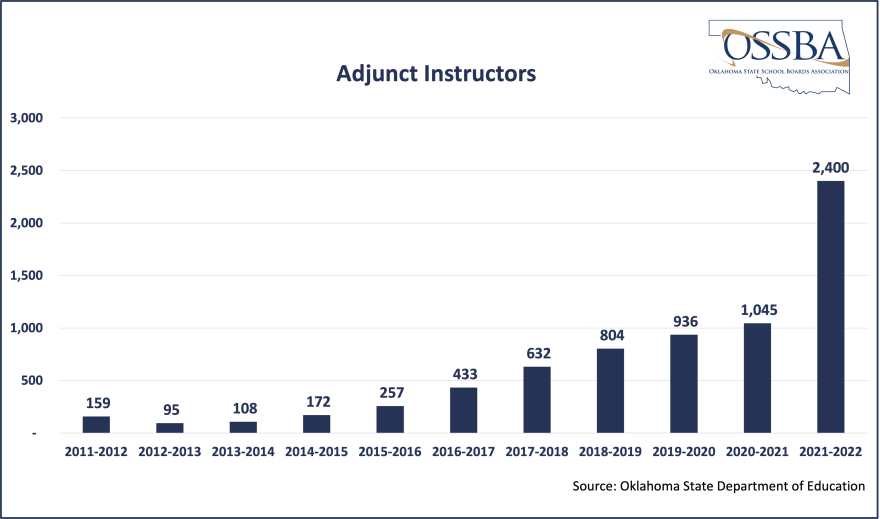

Five years later, it appears teachers’ threats to leave have become reality. Oklahoma’s in a record teacher shortage with around 4,000 emergency certifications issued last year and a 1,400% increase in adjunct instructors — who have no state requirement for teaching certification or a college degree.

Teachers saw some pay increases and increased classroom funding over the last five years, but compared to the rest of the country, Oklahoma is third-to-last in per-pupil spending.

But even though funding measures advocated for by walkout participants were stymied largely by Republican lawmakers, Oklahoma’s GOP is now authoring record-level education funding measures that include teacher raises, along with a slew of labor rights bills for educators. But the funding bills are far from a done deal — in fact, due to a disagreement in how those bills should operate, there could be no deal at all.

Five years after the walkout, with political squabbling threatening to derail over a half a billion dollars in new education money, will Oklahoma teachers again see their high hopes for meaningful educational funding dashed, due to legislative dysfunction?

Did the walkout change anything?

Edmond Republican Senator Adam Pugh chairs the Senate Education Committee and authored several of the bills aimed at attracting and retaining teachers. As a freshman senator during the walkout, he said he was trying to “reconcile his brain” around the frustration from teachers, given the legislature had already passed a pay raise before the walkout.

But for Pugh, the walkout conversations never ended.

“I thought, well, let me go be a conduit in my community to continue that — it doesn’t have to stop just because this is over,” Pugh said.

Pugh said the walkout spawned lasting relationships with educators in his community — such as two teachers he met at the walkout. He visits their second and third grade classes every year for a civics lesson and brings those classes up to the Capitol.

“And that was all born out of that time [the walkout] and that relationship-building. So I know for myself, it was an experience that forged a lot of really good, important relationships,” Pugh said. “And it’s important to note that they weren’t just relationships built on 100% agreement, because that’s not what good relationships are built on, right? They’re built on empathy and understanding and the diversity of our perspectives and how we appreciate that and each other. And so that was, I think, just for me, a tremendous part of that experience, during that walkout.”

This legislative session, Pugh is shepherding measures he believes could make a meaningful dent in the teacher shortage: 12 weeks of paid maternity leave (teachers currently get none), a pay raise of $3,000-$6,000 and pay transparency, an expanded mentor teacher program, reform on teacher evaluations and a program to make getting a teaching degree free, among others.

Pugh said though the walkout may not have ended like teachers envisioned, at the legislature, it’s about the long game.

“If you just look at one moment in time and you say, ‘Well, I didn’t get enough,’ then, you know, I understand that view,” Pugh said. “But I think if you look at what’s happened since and look at the big picture… Based on where we were to where we are, yes, I think [the walkout] made a tremendous impact. Because we’re now looking at almost a doubled education budget in essentially half a decade, which is pretty amazing, I think, for the state of Oklahoma."

Other lawmakers aren’t as convinced. Democratic Senator Carri Hicks is a former elementary teacher. Though she began her campaign in 2017, she and 64 other Oklahoma educators ran for state office following the walkout. And after the November 2018 election, the legislature’s “teacher caucus” grew from nine to 25 members.

Hicks said she worries Oklahoma educators may be given “false hope” the state’s legislature will come through.

“The reason that I kind of have, you know, a bad feeling in the pit of my stomach, if you will, is just because I’ve seen so many times when it looks like both chambers are working on different variations of this same policy goal and it just gets sideways and therefore nothing moves forward,” Hicks said. “And unfortunately, if those two voices can’t reach an agreement or some kind of compromise, then the rest of us lose out.”

Asked whether Hicks thought the walkout has changed anything long term, she said she’s noticed a change in herself.

“The change for me personally is that level of frustration,” Hicks said. “That we showed up, we showed out, we talked truthfully about the circumstances and the situations that we were facing and nobody believed us.”

Hicks said it was “hard to say” if the legislature believes educators now.

“When we’re looking at, you know, certain folks who are really trying to do positive things for public education, and then in the same breath, you’ve got these massive attacks coming from every other angle,” Hicks said. “It’s hard to hold onto that hope.”

When it comes to having faith in the legislature for education reform, Jennifer Williams said she isn’t holding on to that hope either.

“Right after the walkout, I wrote a blog just to get some feelings out about how teaching is like an abusive relationship,” Williams said. “And they keep taking things away and keep smacking us around, metaphorically. You know, taking money away. And they’re saying, ‘Do it for the kids.’ … And I think that’s what we’re seeing now, is just teachers like, ‘You know what? I don’t have to stay here. I can still do it for the kids. It just won’t be Oklahoma kids.’”

Five years later, there’s a budget on the table we could’ve only dreamt about during the walkout. But, like many of the hopes from those thousands of teachers who flooded the Capitol, that could end up being just a dream too.

StateImpact Oklahoma is a partnership of Oklahoma’s public radio stations which relies on contributions from readers and listeners to fulfill its mission of public service to Oklahoma and beyond. Donate online.