The last three years of Alaina Tahlate's work as the Caddo Nation's Language Preservationist have centered around her learning from the few remaining Caddo fluent speakers. The language, which is a member of the Caddoan family, is considered severely endangered.

Like many Indigenous communities throughout Turtle Island, federal and religious Indian boarding schools had a devastating impact on the Caddo Nation, and later so did the COVID-19 pandemic. The widespread virus resulted in the loss of most fluent Caddo speakers, leaving Katherine Proctor and Edmond Johnson to share their wisdom with all, including Tahlate.

"During my language documentation work, inevitably you end up preserving teachings and history and songs with the language, too," Tahlate said. "Language carries ideas, values [and] worldviews. [It] helps us to understand how our ancestors thought about or try to explain how things are the way they are and why they're that way."

When Tahlate first began working with Johnson, she confided in him about her anxiety to undertake this mission and how much pressure she felt to document as much as possible. As Johnson normally did, he offered advice through storytelling, detailing a time when he felt fearful as a paratrooper in the Vietnam War.

"When we were in Vietnam, flying over the jungle in a helicopter, and it was time to jump out into the forest… he said you only have to jump once to show yourself that you can do it," Tahlate recalled Johnson saying to her. "You don't have to have a doubt in your mind that you can't jump. You can't tell yourself that because you already have."

Proctor, the Caddo Nation's oldest member and one of the last fluent speakers, passed in 2023. Johnson and Tahlate were then left to work together to preserve as much as they could.

Similarly to when Tahlate first started working with Johnson, she was nervous about the undertaking, now having only one fluent speaker to turn to. But Johnson reminded her, "All you can do is your best."

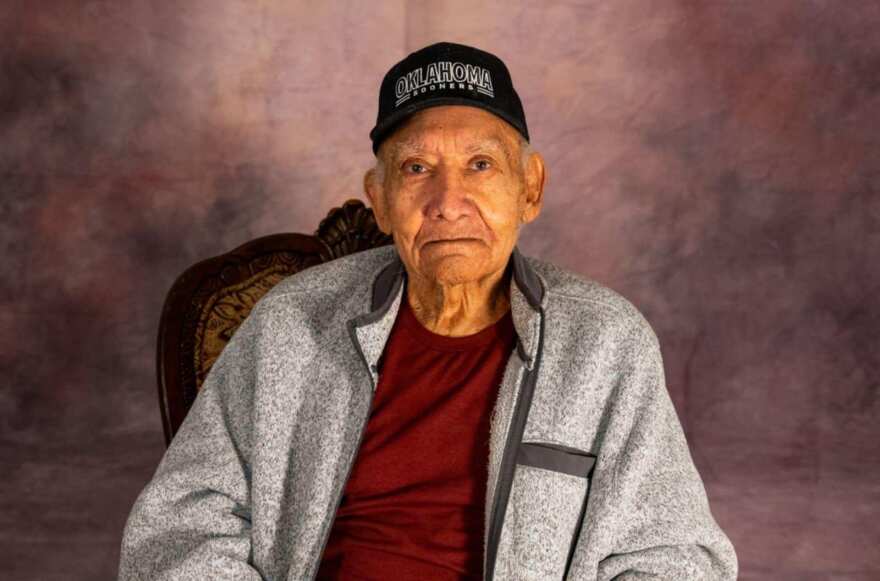

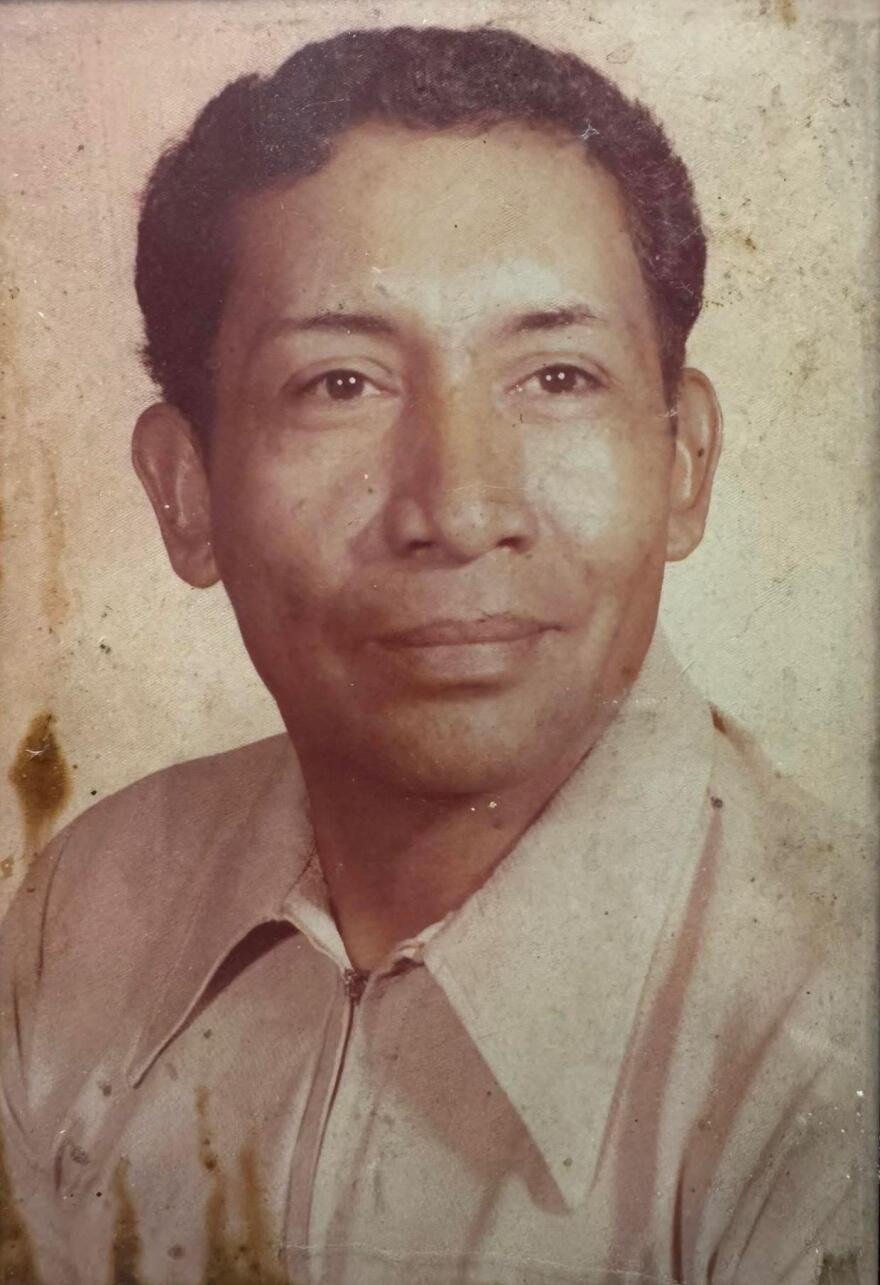

Now, the Caddo Nation is in mourning again, following the passing of Edmond Johnson.

Last Tuesday, the tribal nation honored his legacy during a memorial service, celebrating his life and contributions to their preservation efforts. Johnson was 95 years old.

"Mr. Johnson was not only a vital knowledge bearer of our language and a treasured elder," the Caddo Nation said in a statement. "His passing marks an irreplaceable loss to our heritage, and we extend our deepest condolences to his family and all who mourn with us."

Though he is not her biological grandfather, she referred to Johnson as "grandpa" and noted his teachings have completely changed her life.

"What he wished for all of us is that we just don't give up," she said. "Keep going. Help each other. Teach each other."

Caddo Chairman Bobby Gonzalez said Johnson was his great, great-grandmother's little brother. He used to converse with Johnson in Caddo and will miss being able to speak with him in that way.

"It's a big loss, but at the same time, it was time for him to leave," Gonzalez said. "It's rewarding knowing where he's at because he was a man of God and believed in the Creator. And we're going to continue on and remember the things he said."

Gonzalez noted it's important they continue to safeguard and revitalize what they can because of what it means to their tribal nation.

"Without language, culture and land, you're not a tribe anymore," Gonzalez said.

Looking toward the next generation of Caddo speakers

The spectrum of Caddo language speakers ranges from advanced to beginner.

Tahlate wants to remind her community that the language should not be considered dead. It is simply sleeping in spaces where it was once spoken widely, such as in the home and governance.

"A language is only dead if people do not speak it," Tahlate said.

Following Johnson and Proctor's passing, Tahlate can shift her focus to strategize how best to share the language and have it spoken again in these integral community spaces.

Currently, the Caddo Nation does not have a formalized orthography, as it lacks a standardized spelling system in a dictionary.

Linguists have attempted to create a Caddo dictionary in the past. Still, no such effort has come to fruition, allowing the tribal nation to create a system that is accessible to Caddo citizens.

"The cool thing, I think, about being in this position where we are reclaiming our language is that we are the ones who are going to shape how it's used from here moving forward," Tahlate said. "With the English language, we're kind of stuck with the spelling system that barely makes any sense. But with our Caddo language— being in the position as we are starting from a very low number of speakers— we could make the spelling system however we want it to be, however it best works for us."

She also frequently partners with the tribal nation's cultural educators, creating Caddo language lessons for the little tribal members.

The last generation to grow up with Caddo spoken in their homes is now around 70 or 80 years old, largely due to the negative effects of Indian boarding schools. Tahlate hopes that this next generation can turn the tide.

"The kids don't know anything else. When you present that information to them, it is something that is just a part of their life, part of going to childcare, and it's a beautiful thing to see," Tahlate said. "When these little ones who are learning Caddo right now are grown up, they might speak to their children using Caddo language for the first time in 80 or 90 years, you know, a new first language Caddo speaker where the Caddo language is one of their languages of the home."

Regardless of the starting point, Tahlate hopes Caddo citizens do not face barriers to language learning. It is a part of reclaiming what was once forcefully taken, and she said there should not be shame in beginning the process from square one.

"People will put themselves down from speaking [the language]. They will give up and be mentally defeated before they even want to try because they're scared." Tahlate said. "You are still good enough even if you are not fluent. The point is to speak no matter how much or how little you know."

This report was produced by the Oklahoma Public Media Exchange, a collaboration of public media organizations. Help support collaborative journalism by donating at the link at the top of this webpage.