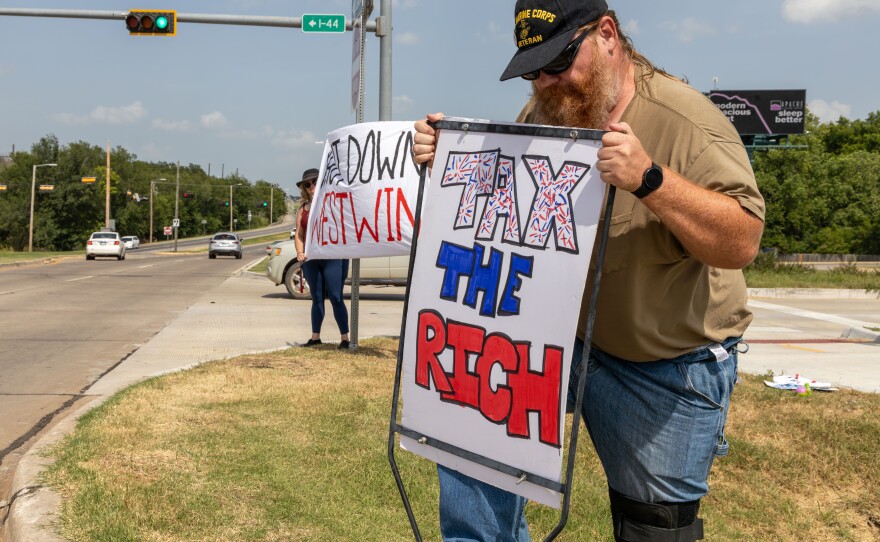

About a half-dozen activists line a bustling intersection near the Comanche Nation Casino in Lawton, united in their fight against city leaders and their decision to support Westwin Elements, a nickel refinery in the southwest Oklahoma city.

Chants for the collective fight came in waves on the scorching mid-July afternoon — phrases such as "Shut Westwin down" and "People united will never be divided." Cars and semi-trucks passed by in rush hour traffic; some honked in support and others in opposition.

Kaysa Whitley, the coalition coordinator of Westwin Resistance, held up a sign among the small flock of activists, with the phrase: "Honor the Earth." This phrase is also the name of the Indigenous-led, global coalition supporting Whitley's position at Westwin Resistance.

"One of our relatives from the Philippines recently reminded me that we're not defending nature," Whitley said. "We are nature defending itself."

![Kaysa Whitley (Kiowa/Absentee Shawnee) walks around the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge on July 17, 2025. It's about 13 miles away from the Westwin Elements demonstration plant. "[There's] something about these mountains, something about the land, the area. It calls to me, and I just always end up coming back here," Whitley said.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/d605625/2147483647/strip/true/crop/6456x4304+0+0/resize/880x587!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Ffe%2F3f%2F16a4479442f593343cb92bc054cb%2Fosu0013-enhanced-nr.jpg)

Some tribal citizens and residents in the area have denounced Westwin Elements, fearing its potential harmful effects to the land, air and water. The demonstration plant produces carbonyl nickel powder, nickel briquettes, and nickel sulfate, which can eventually be used in aerospace defense technology, stainless steel and batteries for phones and electric cars. It does so through a closed-loop system, which creates a dangerous substance called nickel carbonyl for part of the process.

Whitley, who is Kiowa and Absentee Shawnee, has helped lead the charge in this pushback against the startup company and city officials who supported it.

"Our city officials have really made a career out of ignoring people like me… women of color, Indigenous people, people of color," Whitley said.

The frustration Whitley voiced stems from a long, tempestuous history of what Oklahoma State University History Department Head and Professor Brian Hosmer calls "differential power." He explained that decisions affecting Indigenous communities historically did not need approval from Indigenous people and that oppressive power persists today.

"If you look at tribal nations and the development of substantial economic capacity and building schools and health care… and then the effort by the governor and others is to change the rules," Hosmer said. "It's not that Indian people don't know how to do things; it's that the rules get changed."

'One of the biggest land grabs in that era': How the rules started to change for the KCA tribes

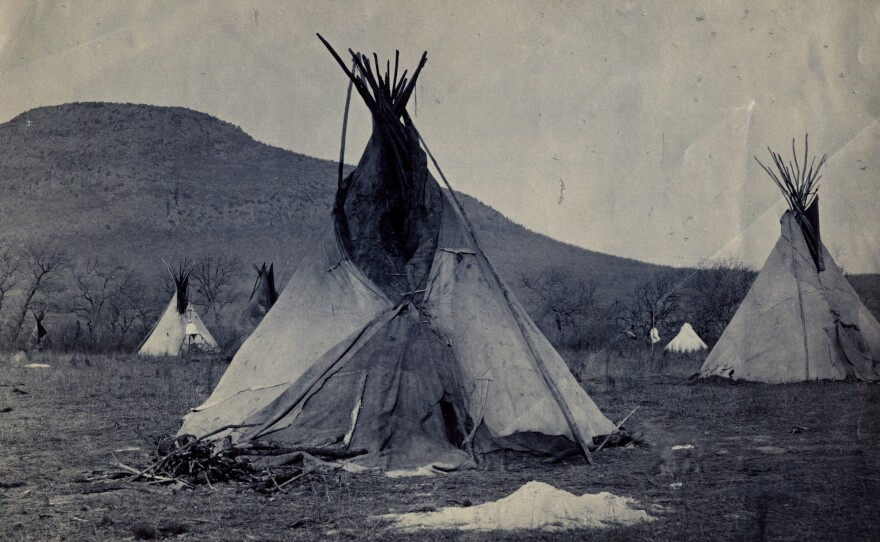

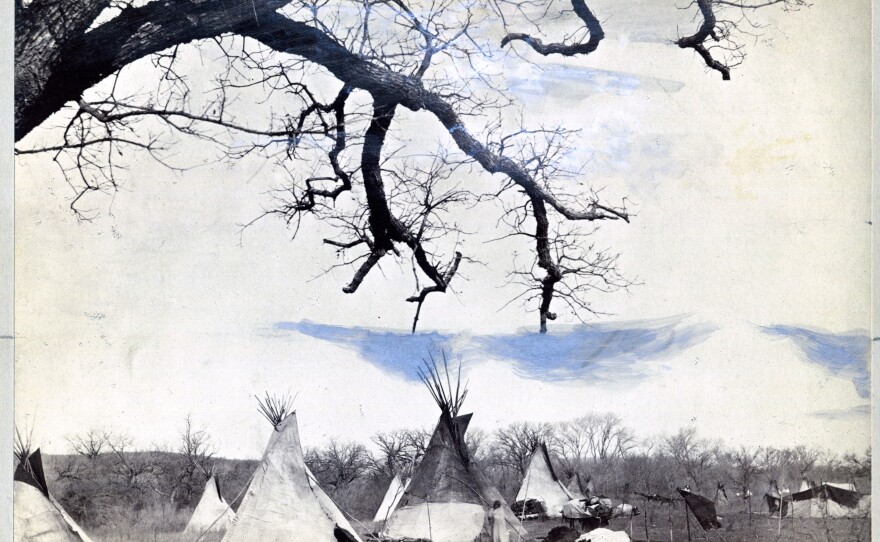

Back in the late 1860s, the Kiowas, Comanches and Apaches reached an agreement with the federal government in the Medicine Lodge Treaty, which established the boundaries of the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache reservation in southwest Oklahoma, spanning 2,968,893 acres.

KCA tribal members witnessed the shrinking size of their ancestors' homelands, along with the decline of the buffalo population, which was integral to their people's way of life. The herds were rapidly declining due to the swift expansion of industrialization and the railroad system, as well as inter-tribal competition. So, the treaty provided "decent enough accommodations to a worsening set of circumstances," Hosmer, the OSU history professor, said.

"[The treaty said] this is their land [and] that there could be no changes to the reservation domain, boundaries, absent a three-quarter vote from the males on the reservation," Hosmer said. "The idea was that you would gather these Plains folks on these lands that were set aside for them, protected for them, and this would be a place where they would be fed and housed and things like that."

But the promised rations don't arrive. They are shortchanged, causing them to hunt in areas outside the reservation, and later, the Red River War.

However, one of the most significant and widely discussed violations of the Medicine Lodge Treaty occurred at the dawn of the 20th century when a Kiowa leader named Lone Wolf decided to file a lawsuit against the Secretary of the Interior, Ethan Allen Hitchcock.

Lone Wolf accused Kiowa interpreter Joshua Givens and the federal government of using threats and deception to persuade tribal citizens to agree to allotment and cede the remaining "surplus land" to the government for non-Indigenous settlement.

He was not alone in his concerns. Formally acting agent for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribe, Captain J.M. Lee, sent a letter to the Indian Rights Association in 1893, siding with Lone Wolf.

"I will say that from earnest, honest, and pecuniarily disinterested witnesses such as Lieutenant Scott and others, I believe that the agreement with the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches was accomplished through threats, cajolery, misrepresentation, and possibly bribery," Lee wrote in the letter.

Hugh G. Brown, a captain and acting Indian agent, also wrote a report detailing the trickery that took place, begging for a "careful inquiry" into the matter.

"Lone Wolf, principal chief of the Kiowas, accompanied by others who had signed the agreement fearing, as he states, that they had been deceived, went to the commissioners and asked to be allowed to see the paper they had signed; this was refused, and their request to have their names erased from the agreement was also refused. The Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches are almost without exception, now that they understand it, earnestly opposed to the agreement," Brown wrote in a letter.

So Lone Wolf argued his case in court.

"[Lone Wolf] is just saying, 'This is your law. This is your constitution, and I'm just asking you to honor it,'" Hosmer said.

But the Kiowa leader ultimately lost the Supreme Court battle in 1903. The ruling solidified that Congress has plenary power over tribes, meaning Congress can treat tribal nations as subjects to be governed rather than sovereign entities.

"Plenary power means that Congress has the same power and authority over Indian affairs as States have over the affairs of their citizens. Congress can limit, modify, or eliminate powers that tribes possess. Congress can even terminate tribal status," according to a University of Alaska Fairbanks Tribal Governance resource.

Due to the Supreme Court ruling, Congress could proceed with enforcing allotment. In the case of the KCA reservation, most of the land was considered surplus and given to non-Indians.

"It's one of the biggest land grabs in that era," Hosmer said. "This is one of the things that I think is not discussed enough in terms of the history of allotment."

The KCA Reservation comprises 2,968,893 acres, but the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache tribes retained only 480,000 acres of that land, ceding 2.5 million acres of surplus land to the federal government for $2 million, according to the Jerome Agreement.

"When I teach this in my classes, I always raise this [question], why not just subdivide the land by the number of people?" Hosmer said. "But no, that's not what happens."

Instead, KCA citizens each received 160 acres, a quarter section of land.

The Lone Wolf ruling remains a sore spot in KCA history and Indian law at large, limiting tribal sovereignty today as Congress's plenary power over tribes is still currently enforced. Hosmer called it one of the "most devastating cases in American jurisprudence."

For Kiowa Chairman Lawrence Spottedbird, it is something with which he strongly disagrees.

"The only person or the only entity that has plenary authority over any person is God himself, and Congress is not God," Spottedbird said in an interview. "How can a body in a democratic society have plenary authority over a select group of people? That's not a democracy."

How the Lone Wolf ruling and a 2005 appropriations bill restrict KCA tribal sovereignty today

Forrest Tahdooahnippah is the Comanche Nation Chairman, who spent more than a decade before his current role practicing and teaching law in Minnesota. He also led a team at the law firm Dorsey & Whitney LLP, serving as the tribal attorney for the Comanche Nation for over five years.

In the past, he said he has assisted tribes with Treatment as a State applications, which can be a powerful tool in tribal environmental protection and could have been a way for the Comanche Nation to fight back against Westwin Elements.

"What the EPA recognizes is that pollution can be migratory, right?" Tahdooahnippah explained.

"Like if I build a polluting smokestack on the border of two states, that's going to cause a problem for the downwind state….They have, through the federal law, ways of arbitrating these disputes between jurisdictions. And tribes can even apply and get Treatment as a State status, so that if there is something that is upwind or upstream and the pollution goes onto tribal land, even though the activity isn't itself occurring on tribal land, tribes at least have a way to voice their concerns and get a seat at the table and have some sort of dispute resolution through the EPA."

However, the Comanche Nation does not have TAS. It is also challenging for them, and other tribes in Oklahoma, to obtain due to a midnight rider that former Republican Senator Jim Inhofe tacked onto an appropriations bill two decades ago.

TAS authority, similar to that of a state, ultimately allows tribes to operate and administer environmental programs and conduct permitting on their lands, according to Earthjustice attorney Mike Freeman. But thanks to Inhofe's legislative maneuver, tribal nations can only receive TAS designations if a Memorandum of Understanding is reached with the state.

"Because of The Midnight Rider, Oklahoma basically has a veto over tribes getting Treatment As a State," Freeman said.

In addition to KCA tribes not having TAS authority, an Oklahoma court has most recently ruled that the KCA reservation is disestablished, thereby weakening the justification for the tribes' jurisdiction.

"[An industrial company, such as Westwin Elements] wouldn't necessarily need approval from the tribes if the reservation was intact, but the tribes would have a much better argument that their approval was required," Tahdooahnippah said.

Despite the reservation's legal standing, KCA leaders actually acknowledge their shared reservation as established.

Since working for the nation, Tahdooahnippah has observed that tribal citizens may blame government leaders if outcomes do not favor them, as was the case with Westwin Elements.

"I think from our tribal members, sometimes they don't understand how stacked the deck is against us," Tahdooahnippah said in his office.

Some of the blame is warranted, as former Comanche Nation Chairman Mark Woommavovah did publicly express approval for the critical minerals refinery at a Lawton city council meeting, sparking backlash in the Comanche community.

However, now Tahdooahnippah is the new chairman, and he said there is little the tribal nation can do.

"Unfortunately, the status quo is not to recognize our sovereignty or our jurisdiction over the broader area," Tahdooahnippah said. "And instead, our jurisdiction has been very cabined to these little checkerboard areas, which I don't agree with."

Checkered jurisdiction on the KCA reservation is primarily a result of allotment and the 1903 Supreme Court decision that Lone Wolf fought valiantly against, and has resulted in different types of land ownership, which broadly include:

- Trust Land: As the name suggests, this type of land is held in trust by the federal government to benefit the tribe. Specifically, the Department of the Interior holds title to the land, which the tribes then govern and potentially profit from through certain tax credits and discounted leasing rates. Trust lands are often exempt from state laws.

- Restricted Fee Land: This kind of land is technically "Indian country" because a tribe or an enrolled tribal member holds the title to the land. Through the fee-to-trust land acquisition process, restricted fee land can be converted into trust land. If it is sold or leased, it needs the Secretary of the Interior's approval.

- Fee (Simple) Land: A person, tribe, or other entity holds the title of this land and can make decisions about it — sell, lease or develop — without having to consult the Department of the Interior. Because of this, fee land is considered the highest possible type of property ownership.

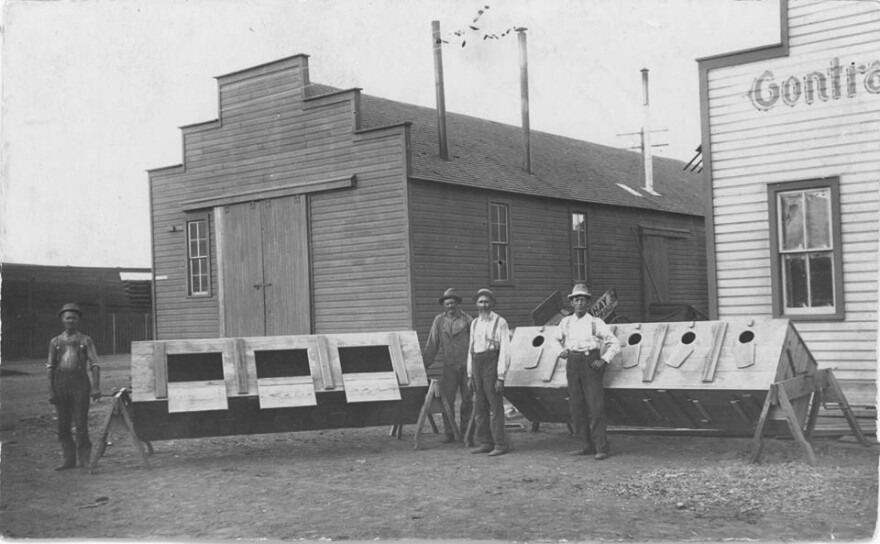

The Westwin Elements demonstration plant is situated on a plot of fee simple land that Edy Carter, who resided in Indian Territory at the time, won in a lottery in 1901. The title passed through different hands over the years, ending up in the possession of the Lawton Economic Development Authority, minimizing KCA tribal control over those lands.

'Not here to be a part of their system:' Westwin Elements resistance efforts continue

Whitley, Westwin Resistance's coalition coordination, teamed up with other local resistance groups to push back against Westwin Elements during their July 21 bridge demonstration protest.

Both Westwin Resistance and Lawton Resistance had members present at the demonstration, recognizing that they are stronger when united.

"They reached out and wanted to be a part of it because they wanted to actually show support for our fight and for our city…it's not just an Indigenous issue," Whitley said. "At the end of the day, the Indigenous people didn't sit down to sign treaties by themselves. A lot of the people who are here now, who are community members, are actually descendants of people who sat on the other side of my relatives."

Whitley has received some positive feedback for her work. But she said she would not need to lead these grassroots efforts if tribal leadership stepped up and if Indigenous people had a guaranteed seat at the table.

"By thinking that we have to play their game in their field, that's a part of what's leading to our demise," Whitley said. "We as people, as a collective, have to stop that. We're not here to be a part of their system or to even uphold it. We exist outside of it."

Whitley said her ancestors didn't win fights by continuing with this oppressive system. They won by standing against it.

This story is supported by the Earth Journalism Network. The next feature in the series will highlight what is at stake for both the KCA community and Westwin Elements — special thanks to Oklahoma State Historian Matthew Pearce for his research assistance in reporting this story.

This report was produced by the Oklahoma Public Media Exchange, a collaboration of public media organizations. Help support collaborative journalism by donating at the link at the top of this webpage.