For Oklahomans accused of low-level crimes like possessing small amounts of drugs or public intoxication, getting out of jail free while the case is pending often depends less on the nature of the charge than on what county they are arrested in.

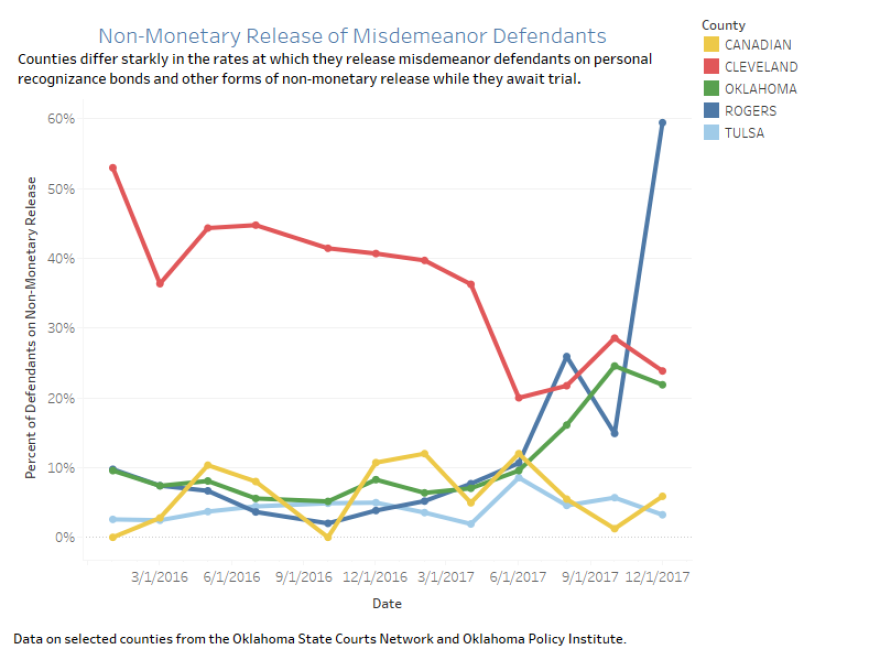

Court data shows that counties have widely varying rates of pretrial release of misdemeanor defendants without requiring cash bail.

The result is that in many counties, hundreds of low-level defendants sit for days or weeks in jail because they can’t afford to post bond of even a few hundred dollars. That can place their jobs at risk and cause family hardships. The county also spends hundreds of dollars incarcerating the inmate and may face a jail overcrowding issue.

In other counties, lock-up times are shrinking. Within limits, inmates with minor charges are given a so-called “nonmonetary release” and must appear for trial on their own, or be arrested and jailed again. The release can come in various forms: on personal recognizance bonds approved by a judge, “book and release” at the jail, or citations by officers instead of arrest.

More counties are exploring these options and others because their jails are full or costing taxpayers more. County officials are concerned that statewide criminal justice reforms that reduced drug possession penalties will flood local jails with misdemeanor arrestees.

In the meantime, a patchwork of policies creates inequities in detention.

No-Bail Release Rates

Oklahoma Watch requested pretrial release data for 12 counties’ jails from the nonprofit advocacy group Oklahoma Policy Institute, which maintains a database compiled from Oklahoma State Courts Network records.

The data from the 12 counties – a mixture of rural and urban ones – found sometimes large disparities in the percentage of released misdemeanor defendants who were not required to post bail. In 2017, for example, Canadian County granted no-cash releases to 8 percent of misdemeanor defendants let out of jail. The rate was 14 percent in Oklahoma County, 30 percent in Cleveland County, 5.5 percent in Tulsa County and 63 percent in Comanche County, the court data shows. In Adair County, no recognizance releases were granted.

In 2017, however, some counties began altering their approach, wanting to step up no-bail releases.

Rogers County, home to Claremore, made a dramatic shift.

The county’s focus on pretrial release began last year when it decided to look for ways to ease overcrowding in its chronically packed jail. A report from the Vera Institute of Justice, a New-York based group that studies incarceration and criminal justice, found the 250-bed jail averaged around 280 inmates, sometimes rising above 300.

Like other counties across the country, Rogers County had been releasing people from jail based on the ability to pay cash bail rather than making individualized determinations of flight risk or danger to the public.

Bail amounts are supposed to reflect a person’s likelihood to abscond, but that often isn’t the case. Nationally, six in 10 jail inmates haven’t been convicted of a crime and are instead awaiting trial, according to the Vera Institute.

A one-day snapshot captures the situation Rogers County faced. On March 8, 2017, the county jail contained 276 inmates; of those, 209 had a bond amount set. The others were being detained for other agencies, serving a sentence or held for another reason.

Of the 209 inmates, 36 were being held on bond amounts of $5,000 or less, meaning they likely would have gained release if they had come up with $500. The bond for half that group was $2,500 or less. In some cases, people were in jail for more than five days, when just $250 would have gotten them out.

In May, Rogers County Judge Sheila Condren, then the district’s presiding judge, issued an administrative order that launched a nonmonetary release program. It is tailored for nonviolent offenses, allowing people facing charges like simple possession, driving under the influence or petty theft to be released on their own personal recognizance if they cannot post bail. It has caveats: DUI offenders, for example, can only be released for misdemeanor cases, not those involving negligent homicide. They are released only after a six-hour sobering period.

Inmates with warrants outside the county cannot qualify; nor can those who face certain other charges.

Seven months later, during December 2017, nonmonetary release was granted to nearly 60 percent of Rogers County’s misdemeanor defendants who left jail. That compared with 3.8 percent in December 2016.

“I think we’re on a path where at least we can stave off building a new jail,” Condren said in an interview.

The Vera Institute also recommended Rogers County use “book and release”, in which jailers or officers book a person or issue a citation but release him or her without incarceration. But the county hasn’t yet implemented this program.

Largest Counties

In contrast to Rogers County, the state’s largest urban counties are making less dramatic progress in their plans to reduce jail population by increasing nonmonetary release of defendants.

In December 2017, Oklahoma County granted no-bail releases to 22 percent of misdemeanor defendants released in December 2017, compared with 8 percent a year earlier, court data show. And by year-end, its jail population stood at a record low of 1,560, The Oklahoman reported.

The increase has come through a combination of efforts by judges, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, public defenders and county commissioners. The shift followed a report by the Vera Institute for a task force of community leaders looking to reduce the jail population and make other changes.

In Tulsa, pretrial release efforts are more stagnant. In December 2016, 5 percent of those released from the Tulsa County Jail did not have to post bond. A year later, the rate was 3 percent, or 11 people.

As in Oklahoma County, leaders in Tulsa County commissioned a Vera Institute study that last year recommended reducing jail admissions and lengths of stay for those with low-level charges, and creating a pretrial release protocol not based solely on ability to pay bail.

Like Oklahoma County, Tulsa County has a dedicated pretrial release program. But the Vera report found that it’s “underutilized” and called for more changes, such as automatic releases after booking for certain charges and greater use of citations. Tulsa County has yet to implement some of the key recommendations in the report.

Tulsa County Chief Public Defender Corbin Brewster said his office is becoming more aggressive in asking ask for clients to be released, but said that opposition from the district attorney’s office often stymies efforts. Without opposition, he said, those clients would be able to get out.

Brewster wants to see the court use personal recognizance bonds more often, which would allow someone to be free without having to post cash. He hopes all of the parties in the justice system will be more collaborative.

“People are waking up and realizing this is a very unfair way to run the system because it affects people who are indigent and holds them in jail and has extreme effects on their life,” he said.

The county has taken some steps, such as requiring the bond amount for cases with multiple charges to be based only on the most serious charge or the one with the highest bond amount. This prevents so-called “stacked bonds,” where an offender racks up a large bond for multiple similar offenses. s of the same nature. That doesn’t apply to 22 mostly violent offenses.

Tulsa County District Attorney Steve Kunzweiler said to increase nonmonetary releases, his office tries to be proactive in identifying cases that will get a recommendation for probation at sentencing. Even if no plea is made, he said, the office coordinates with the defense to get the defendant out on a personal recognizance bond. That typically requires petitioning the court.

Kunzweiler had little comment on Vera’s recommendation for book and release, saying implementing any recommendations would involve people besides him, including judges.

“We have basically a bond schedule that’s been set, so if there’s any modification of that, it has to go through the judges,” he said.

Tulsa Sheriff Vic Regalado said in addition to pretrial release, keeping recidivism down is a key to keeping the overall population down in addition to pretrial release.

“We’re thinking about what we can do to help with that rehabilitative process,” he said.

District Judge William J. Musseman, the district’s presiding judge, said he wasn’t ready to make a statement yet on the “book and release” recommendation.

He said improving the situation will involve looking at all aspects of the criminal justice system and is a “work in progress”.

Statewide Interest

Ray McNair, executive director of the Oklahoma Sheriffs’ Association, said he’s been getting requests from counties around the state for information about bail and bond schedules and what’s working elsewhere in the state.

He attributes the inquiries to criminal justice reforms that make it more likely for offenders to serve time in a county jail than in a state prison. For example, with drug possession reclassified as a misdemeanor under State Question 780, people are more likely to do time in jail.

“All we’ve done is shift the burden off the state correctional facilities and put it back on the county facilities,” McNair said. “Unfortunately, we can’t go the state Legislature and say, ‘Give us money.’”

As the demands on county jails increase, a different way of thinking is needed, McNair said.

Failure to Appear

Pretrial release approaches can run into complications.

For example, low-level cases now take longer to get resolved, slowing down the docket, said Rogers County District Attorney Matt Ballard, adding he still supports the program.

“If somebody has a job and has connections to the community, certainly they need to be out,” Ballard said. “It’s more work to try to look at those cases, but that’s something we’re willing to do.”

Another issue is that some people don’t show up for court hearings because they get the wrong date from the jail or don’t get a court date and fail to check.

Rogers County plans to create a notification system that will text upcoming court dates to participants. Getting that in place is three to six months away, said Condren, the district judge.

“It’s an ongoing process for us to figure out,” Condren said.