Forty-five years ago, LaNelma and Ray Johnson accepted the Bahá’í faith, and its tenet to serve humanity and the oneness of mankind. That desire took them to India in 1971, where they taught children ages five to 18 at a small, rural school in Panchgani.

“Some of the children were there because they were orphans, and some were there because they came from war-torn countries,” LaNelma Johnson says. “We really felt like we could do a service there with these children.”

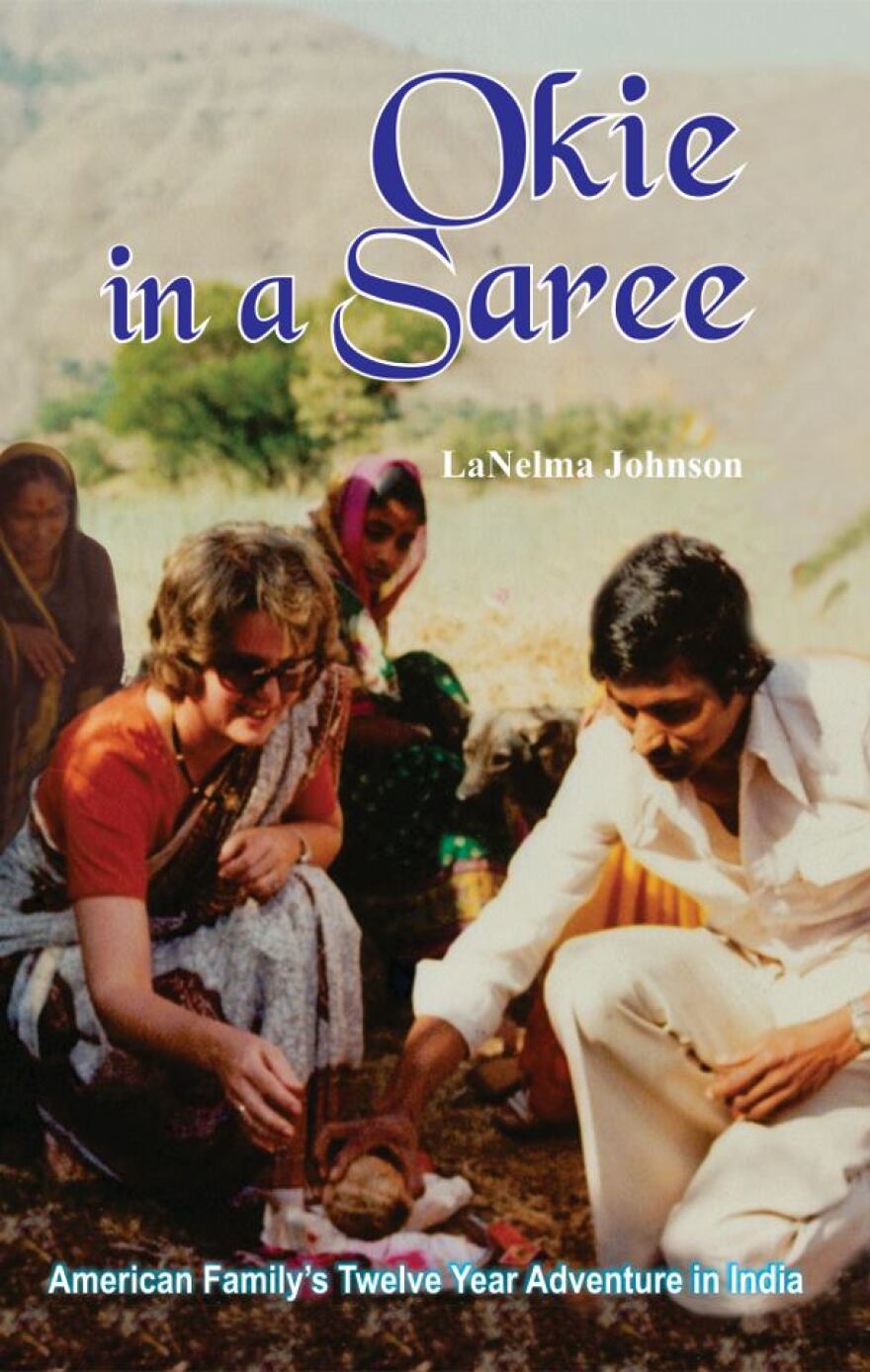

Johnson told the story of her family’s 12 years in India in her memoir Okie in a Saree. The couple set out to consciously recruit female students from all over India, since they weren’t afforded the same educational opportunities as boys. India’s caste system had already been illegal for decades, but reforms were slow to trickle down to rural villages.

Johnson says a woman in India’s lowest Harijan caste cleaned the toilets in the New Era School every morning alongside her ten-year-old daughter. They realized education might be this girl’s way out of her caste, so they offered her a scholarship.

“She continued to do her work in the school before school started in the mornings,” Johnson says. “But that little girl went on to become the very first Harijan to work for Air India, and she became an air hostess when she finished her school.”

The Johnsons were only 31 when they arrived in Panchgani, and locals were very forgiving of the first Americans in the village. When they introduced themselves to dozens of students’ parents, they had no idea who practiced what religion, or who was a part of what caste.

“The man that was translating for Ray came and said, ‘Sir, there has been a miracle here today’,” Johnson says. “’The Harijans were sitting next to the Brahmans (the highest caste), and next to Hindus and Muslims and Buddhists, and they would never do that in our community, outside.’ But whenever the parents or anyone came in through the doors or gates of New Era School, they all knew that everyone was treated equally, with dignity and respect.”

Indian society’s treatment of women has dominated headlines in recent months. In September, four men were convicted and sentenced to death by hanging for the high-profile 2012 gang rape and murder of a female student on a bus in New Delhi.

Johnson says this negative perception of India doesn’t necessarily match reality in the world’s second-most populous country. She and her husband traveled to the Dharavi slum in Mumbai 18 months ago, and saw what she described as “wonderful things.”

“It’s still called a ‘slum’, but they have schools, they have churches, they have synagogues, and temples and mosques and hospitals, and we met children with school uniforms on, speaking English, and going to school,” Johnson says. “We came away with a feeling that this is a community. These people actually feel safe here, and even if they had the funds to rent something in the city of Mumbai, they probably wouldn’t leave.”

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On reconciling tradition, ignorance and education

The children in our school were growing up side to side and they didn’t even realize their best friend might be of a different caste, or all the children were treated the same, no matter what faith they were. This school was owned by the Bahá’í faith, but we were open to all faiths, and so I think through the education system when they left there, if they could break out of a caste system and that’s what’s happened in India. I think that, you know, many people have come out of their… if it’s a low caste, they’ve been educated and they’ve been able to go on and break out of that and improve their lives.

On perception vs. reality of violence against women in India

I actually feel safer in Bombay, Mumbai and parts of India, than I do in the United States, in some cities, in some areas. The issue of the young girls and prostitution and whatever they’re taken for, that happens everywhere in the world and I think when those incidents happen, it is there and it’s a terrible issue and I think they’re working on that, but the population of India is so great and the poverty issue is so great that I don’t know when it will be resolved, but the people of India are absolutely wonderful and the culture is wonderful and I think, you know, things have greatly improved for females.

____________________________________________________

KGOU relies on voluntary contributions from readers and listeners to further its mission of public service with internationally-focused interviews for Oklahoma. To contribute to our efforts, make your donation online, or contact our Membership department.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

SUZETTE GRILLOT, HOST: LaNelma Johnson, welcome to World Views.

LaNELMA JOHNSON: Thank you, it’s nice to be here.

GRILLOT: So you have written this very interesting book about your twelve years that you lived in India. Tell us a little bit about how you ended up in India. You’re from Oklahoma, grew up in Perry, what took you from there to India? Tell us about this fascinating story.

JOHNSON: Thank you. Well my husband, Ray Johnson and I, accepted the Bahá’í faith while we were at Stanford University in 1968, and one of the important tenets of our faith is service to humanity and the oneness of mankind, the oneness of religion, the oneness of the world, and, so, we decided that we wanted to give our children and ourselves an experience in another culture and serve humanity and since we were in the field of education we thought we should search for school, and we found a small school in India, the New Era School, and in 1971 we took our three small children, three, five, and seven at that time, to India, to serve this school, and we had children, we grew to have children from thirty countries and all faiths were represented. So, it was a wonderful experience for the kids to grow up in that area.

GRILLOT: So, from your service, your interest in service, given your background in education, how did you pick this school and this country? Just by searching? What is it that drew you? Was there something that spoke to you about India? Had you visited? I mean, because that’s a huge move taking three small children and your entire family and uprooting and traveling, you know, the other side of the planet, so what was it that spoke to you about that particular place and location and that time?

JOHNSON: Well, my husband’s dean, Dr. Dwight Allen, who is a very well-known international educator, as well as in the United States, actually told us about this small school because he had just visited there in 1970, and he suggested that we check it out and it was owned by the, the school was owned by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of India. So we contacted them and we were invited to come and visit. So, first, Ray went to a visit, and then a few months later I went to visit and we decided we were just drawn to the school, I think mostly because of the children.

GRILLOT: And what was it about them that you felt like they needed you? They needed your education? What was it that you were going to provide them?

JOHNSON: Well, this was a boarding school, and children were there from ages five through high school, and they were far from home, and some of the children were there because they were orphans and some were there because they came from war-torn countries, and we really felt like that we could do a service there with these children. So, that was basically the reason that we wanted to go there and we did just fall in love with India and the children right away.

GRILLOT: So, what was your experience with the educational system, in particular? Because there have been a lot of concerns over the years about the Indian education system and equal access and questions of lack of equity across the country in terms of the educational opportunities that are provided to children. So what is it that you saw and experienced? Did your work contribute to any kind of solution?

JOHNSON: Well, I think it did, because we did have Indian children from the village where the school was located, Panchgani, India. The male children were of the majority when we arrived and in the boarding school, also, the male children were the majority when they were coming to be in the boarding from other parts of India, so we set us about to really, consciously, recruit female children from all over India , and also from the village, to be these students, and, so that issue was definitely there. Female children were not given the opportunities that male children were given. I have a short example on what happened. This has to do with caste system, changing the subject bit, but we had a sweeper in our school who cleaned the toilets every morning and she was the lowest caste, the Harijan caste. She had a small daughter who worked with her who was about ten years old, and we decided if we could get that little girl to come to our school on a scholarship, she might be able to break out of her caste system if she were educated. So the mother did agree and that little girl started the school, she continued to do her work in the school before school started in the mornings, but that little girl went on to become the very first Harijan to work for Air India, and she became an air hostess when she finished her school.

GRILLOT: Well that’s a great success story. You raise two important issues here that I’d like to ask you about and that is gender equity in schooling, but also in general in India, but also the caste system and the socioeconomic discrimination that exists. Over your time there, how did you see that evolve or change, if at all? I mean, did you see India, kind of working to the point where these were less relevant or less concerning or, did you really not see much change during your time there?

JOHNSON: You know, in India, we say some things never change and some things always change. Yes, I think we did see change in that area. Of course now, the caste system is illegal, but sometimes in some places it does still exist, but I think that in our school, particularly, we didn’t have that situation. In fact, because of ignorance and lack of understanding of the culture when we first arrived – we were only 31 years old – and we made a lot of mistakes and the local people were very forgiving, but we did have a gathering of our local day parents in our school to introduce ourselves. When we first arrived, we were the first Americans in that village, and they all came into the school. There were about forty parents, and more than that if both these parents came, maybe sixty people, and they were all seated side-by-side. We didn’t know who was what religion, who was what caste, and they were served tea and snacks, and at the end of that gathering, the man that was translating for Ray came and said, “Sir, there has been a miracle here today,” and he said, “What miracle was that?” and he said, “The Harijans were sitting next, the lowest caste was sitting next to Brahmans the highest caste, and next to Hindus and Muslims and Buddhists, and they would never do that in our community, outside.” But whenever the parents or anyone came in through the doors or gates of New Era School, they all knew that everyone was treated equally, you know, with dignity and respect. So the word quickly spread throughout the village. So in our small community, we did see a big difference, as the years went by, particularly in our school with the children.

GRILLOT: And so this is largely related, I guess, to education, right? With education, with, you know, greater opportunity comes a more open mind and an ability to overcome these kinds of differences.

JOHNSON: I think so, because it’s through tradition and ignorance, really, and lack of education and understanding that with the education and the children in our school were growing up side-by-side and they didn’t know, they didn’t even realize their best friend might be of a different caste or all the children were treated the same, no matter what faith they were. This school was owned by the Bahá’í faith, but we were open to all faiths, and so I think through the educational system when they left there, they could break out of a caste system and that’s what’s happened in India. I think that, you know, many people have come out of their… if it’s a low caste, they’ve been educated and they’ve been able to go on and break out of that and improve their lives.

GRILLOT: So, think about India, today. I mean, how connected are you still to India, today? I mean are you up to date on, kind of, what’s going on in the news, because India’s been in the news, lately, with things that aren’t really all that pleasant. Violence against women, for example, let’s go back to this issue of girls and their access to education, I mean, there’s a tremendous amount of discrimination and violence, still, against women today. Are these things that, you know, your approach in one little village really needs to grow across India in order to address these kinds of problems?

JOHNSON: Well, to answer your first question, we’re very connected, still, to India. We’ve been back to India many times, and we are so connected with the students that were with us during those twelve years that, you know, we traveled the world, we see our students and so forth, and also our son, Craig Johnson, who was five years old when we went to India, after 20 years he’s been with the American school system, first of all, for eighteen years, but three years ago he went back to India. He is a superintendent of the American School of Bombay, so, yes, we’re very connected. We were there just a year and a half ago. To answer your second question about the female students and those issues that are, you know, happening today, I actually feel safer in Bombay, Mumbai and parts of India, than I do in the United States, in some cities, in some areas. The issue of the young girls and prostitution or whatever they’re taken for, that happens everywhere in the world and I think when those incidents happen, it is there and it’s a terrible issue and I think they’re working on that, but the population of India is so great and the poverty issue is so great that I don’t know when it will be resolved, but the people of India are absolutely wonderful and the culture is wonderful and I think, you know, things have greatly improved for females.

GRILLOT: So, this is a negative perception that we, perhaps, see played out in the media in other parts of the world, that doesn’t necessarily match up in real life in India in the sense that, you know, as you mention, these things happen everywhere, it’s not just India, it’s not just poor countries, it’s not just those who struggle, but in all parts of the world, and so, is it a matter of, kind of, how it plays out and how we learn about these parts of the world, that’s really the problem? It goes back to this issue of education, educating ourselves? I mean, are we, ourselves, ignorant of what life is like in India?

JOHNSON: I think so. The typical Indian youths or child would know much more about geography and what is happening in the world than an American child or youth would know, for example, and I think if people would travel and investigate more about what’s happening in the world, they would find out that, you know, things have improved. For example, the Dharavi slum in Mumbai, where Slumdog Millionaire was filmed, everyone’s familiar with that, we took a tour of that slum, which is a city of a million people. A year and a half ago we went there and we saw amazingly, wonderful things that were happening there. People have lived there for several generations and it grew from a small slum to a large slum. It’s still called ‘slum’ but they have schools, they have churches, they have synagogues, and temples and mosques and hospitals and we met children with school uniforms on, cleans speaking English, going to school. We saw so many cottage industries with arts and bread being made that was being sent to Taj Mahal Hotel, which is a five-star hotel, and we came away with a feeling that this is a community. These people actually feel safe here, and even if they had the funds to rent something in the city of Mumbai, they probably wouldn’t leave. It’s very interesting.

GRILLOT: Well I think you’ve definitely told us exactly what we all should know, and that is we need to see these things first hand in order to truly understand them. So thank you so much LaNelma for joining us today and sharing your story.

JOHNSON: Thank you for your invitation, I appreciate it.

Copyright © 2013 KGOU Radio. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to KGOU Radio. This transcript is provided for personal, noncommercial use only. Any other use requires KGOU's prior permission.

KGOU transcripts are created on a rush deadline by our staff, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of KGOU's programming is the audio.